The economic rebound from the 2008 recession is a rising tide that doesn’t necessarily lift all boats. Several sectors are showing mixed-blessing results, including credit card lending, retail, manufacturing, real estate and some financial sectors.

Credit card lending has rebounded since the recession. It looks like a good thing for banks and card issuers. U.S. revolving consumer credit card debt hit $1 trillion this April – within 1 percent of 2008 debt levels – and it’s expected to keep rising through this year and early next. Excessive credit card debt could become a trouble spot for banks and card issuers.

“We don’t know how much credit card debt is too much,” said Matt Schulz, senior investment analyst for creditcards.com. Two forces are at issue, he said: A spike in delinquencies by overleveraged consumers and an increase in consumers who don’t carry any credit card debt at all. Those consumers have concerns about job insecurity, student debt or future health care costs (the number one concern listed in creditcards.com customer surveys).

The Federal Reserve’s series of quarter-point rate increases will begin to factor into the cost of credit card debt. Each Fed rate raises generally get factored into credit card interest rates within a single billing cycle. Though each hike doesn’t significantly impact ability to pay, any increase in the cost of debt “is unwelcome,” Schulz said. “The biggest issue is [the economic unknown]. A lack of control is what keeps people awake at night.”

Then there’s retail. Consumers represent 70 percent of the U.S. economy, and today, more of them are online – 18 percent nationally, and probably higher than that in Massachusetts. The Retailers Association of Massachusetts (RAM) last week headed to the State House to press its case for a sales-tax-free weekend for the state’s retailers.

“Public policy should not incent consumers to go online and buy,” RAM President Jon Hurst said, calling the state’s 6.25 percent sales tax “an anchor around our neck.”

“We have to determine whether [Main Street] storefronts, property taxes and job incomes have value to our policymakers,” he added.

He noted another big-picture disparity: the overbuilding of commercial space. While mega-retailers such as Macy’s and Sears are closing stores, and empty shopping malls are being repurposed to non-retail uses, “We are overstored. We have way too much commercial property in Massachusetts, and we are building more,” Hurst said. He attributes this to the investment allure of commercial space on the part of REITS, while tenants for that investor-funded space are becoming harder to find; “you’re stealing them from someone else,” he said.

Retail has been the largest sector for new entrepreneurs, but RAM isn’t seeing as many as it did a few years ago, Hurst said. Consumers may spend more in 2017 than in 2009, but they’re not necessarily spending it with the local small business. Meanwhile, rent, labor and energy costs are continuing to rise, pushing more small retailers to move their businesses increasingly online.

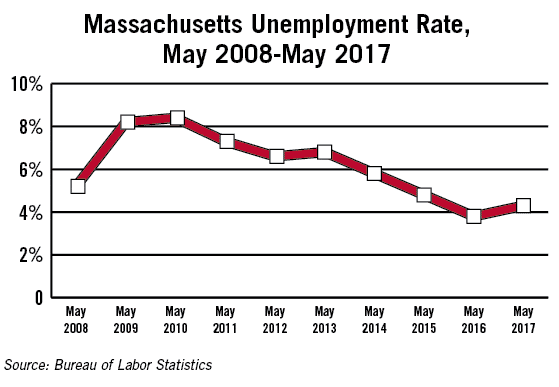

Things are not always as they seem, and that’s hardly more apparent than in the Massachusetts unemployment rate. In part the rise is attributable to people who have been on the sidelines reentering the job-hunting arena. Employers say they can’t fill the number of positions they have available.

The disconnect problem is a skills gap, which could be resolved by an active partnership between employers and training institutions of all types, from academic to private. Christopher Geehern is executive vice president of marketing and communication at Associated Industries of Massachusetts (AIM), which communicates with more than 1,000 employers across the state. He noted there are few standards and no common curriculum for skilled machinists and that it’s hard for nonprofit educational institutions to keep up.

However, there is a growing number of workforce training programs that get support from regional employers. Springfield Technical Community College, supported by companies such as Smith & Wesson, offers a strong CNC program. There’s the Tech Foundry in Springfield, a job training nonprofit founded in early 2014 that partners with area employers. Tech Foundry reported earlier this year that it had a 65 percent placement rate for IT students. The State Workforce Training Fund is a non-industry-specific program paid for from unemployment insurance premiums.

A main sticking point, said Geehern, is the cost of housing where the jobs are. Economic hot spots such as the Greater Boston area tend to have high housing costs that discourage more workers from moving to where the jobs are. “It’s a big issue, and will get bigger,” he said.

Affordability Crisis

Which leads to housing. The Greater Boston Annual Housing Report Card 2016, produced for The Boston Foundation in collaboration with many organizations, including The Warren Group, publisher of Banker & Tradesman, is subtitled “The Trouble with Growth; How Unbalanced Economic Expansion Affects Housing.” The report notes that when the Boston Foundation first began publishing the Report Card 15 years prior, a major concern was a brain drain on the part of young, talented workers heading for cities with more professional opportunities. The most recent report cites an opposite problem, forecasting continued population growth through at least 2030. Where will they all live?

The 2016 report notes that housing supply is not keeping up with housing demand, particularly for low- and moderate-income people. Young people and aging Baby Boomers in search of affordable multifamily housing units are hard-pressed. Families in poverty are on lengthening waiting lists for housing vouchers, and those who have them remain stuck in communities that may lack a robust transportation network to get to jobs – which gets back to the disconnect between job positions and people to fill them. Lack of transportation, coupled with a lack of housing mobility directly correlates with lack of access to improved employment.

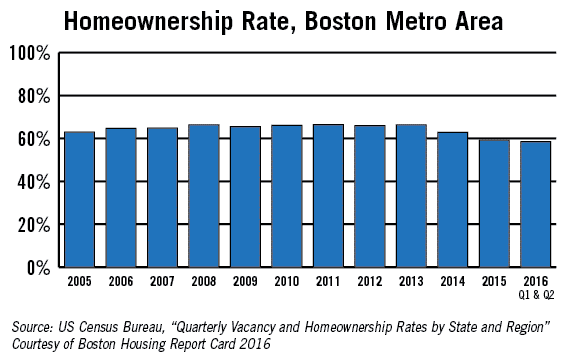

Another disconnect is the forecast boom in house and condominium sales, despite a continued drop in homeownership rates. That’s a problem Greater Boston shares with economic hot spots in the rest of the country. The report cites a drop from 64 percent homeownership in Greater Boston from 2005-2013 to 58.5 percent in 2016. The homeownership rate for 20- to 34-year-olds plummeted from 40.7 percent in 2000 to 30.2 percent in 2014, according to the report.

Another disconnect is the forecast boom in house and condominium sales, despite a continued drop in homeownership rates. That’s a problem Greater Boston shares with economic hot spots in the rest of the country. The report cites a drop from 64 percent homeownership in Greater Boston from 2005-2013 to 58.5 percent in 2016. The homeownership rate for 20- to 34-year-olds plummeted from 40.7 percent in 2000 to 30.2 percent in 2014, according to the report.

The bad news about that: the homeownership decline, if it continues, could adversely impact the assets of Millennials going forward – as well as the stability of communities that depend on high proportions of homeownership to foster civic engagement.

Some good news: the number of Massachusetts communities prohibiting multifamily housing dropped from 308 in 2012 to 114 municipalities in 2016. Additionally, last year the Massachusetts Senate passed housing legislation to provide cities and towns with new tools for planning, zoning and permitting, to encourage re-zoning for more housing in general and more affordable housing in particular. The report noted that the Massachusetts House would need to take up this legislation in its next session.

These are the good news/bad news aspects of the state’s economic recovery. How residents and politicians navigate them will determine not only the state’s growth, but how resilient it will be in dealing with a next, inevitable cyclic downturn.

|

|