Governor-elect Maura Healey and Boston Mayor Michelle Wu talk to reporters after meeting in Wu's office Tuesday, Dec. 6, 2022. Photo by Sam Doran | State House News Service

What do Boston, Somerville, Salem and Northampton have in common?

They all want to significantly limit the future use of fossil fuel infrastructure such as oil and gas hookups in buildings, and they all need state permission to do so. But as it currently stands, only one of those four – or any other communities who could still jump into the pool of applicants – can win the green light from the Healey administration.

The state is gearing up to begin a pilot program in which 10 cities and towns will be authorized to require that new construction and major renovation projects within their borders eschew natural gas, oil and other fossil fuel energy in favor of cleaner electric options, a novel bid to slash the sector’s significant contributions to greenhouse gas emissions.

Nine of the slots in the program are effectively filled, but one slot opened up earlier this month after its previous holder withdrew. Now, Gov. Maura Healey and her deputies face a tricky choice over which municipality should secure the last spot, which could dramatically alter the program’s scope and may serve as a test of the new governor’s commitment to cutting emissions.

Should it be Boston, the state’s largest city and a place where Mayor Michelle Wu has made climate policy a staple of her tenure? How about Somerville, a dense urban center that’s home to significant development, or Salem, where Lt. Gov. Kim Driscoll spent 17 years as mayor? Or perhaps Northampton, which would add a western Massachusetts perspective to a roster currently dominated by the eastern metropolitan core?

Reining in emissions from building infrastructure looms as a crucial piece of the state’s work to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. Buildings contributed about 35 percent of the state’s emissions in 2020, the second-largest of any sector behind transportation with 37 percent, according to state data.

Lawmakers created the program in a clean energy law signed last year by Gov. Charlie Baker, who had voiced concerns that imposing such significant restrictions on the construction sector could slow development and exacerbate a housing shortage.

To qualify, a city or town had to vote in favor of new clean energy building requirements locally and send the state legislature a home rule petition formally asking for permission to implement them.

The 10 spots filled quickly – in fact, each of the home rule petitions arrived before lawmakers had even finished negotiating the final bill – but uncertainty quickly emerged about whether each hopeful city or town would be able to fulfill some affordable housing requirements woven into the final version of the program.

Now, with a key Sept. 1 deadline in the rearview mirror, the field is clearer. Nine communities – Acton, Aquinnah, Arlington, Brookline, Cambridge, Concord, Lexington, Lincoln and Newton – submitted official applications.

West Tisbury, a tiny Martha’s Vineyard town of about 3,000 people, officially withdrew. Town Administrator Jennifer Rand told state officials her community “would very much like to participate in the pilot project but cannot meet the required affordable housing criteria.”

While the initial pathway into the program prioritized communities in the order they applied, the process of selecting a substitute does not follow any rigid queue. The Department of Energy Resources instead has discretion to pick a replacement for West Tisbury.

An administration official said program regulations call for DOER to consider factors such as local support, how a community would contribute to the pilot’s diversity, a municipality’s compliance with the zoning and affordable housing requirements, and localized electric grid investments needed to support fossil fuel-free construction.

The department can give “preference” to communities that meet compliance guidelines implementing a 2021 zoning reform law that seeks to allow multifamily housing by right in parts of MBTA communities, according to the regulations.

Applications for substitute communities are due by Nov. 10, and DOER will pick a replacement to proceed after March 1, 2024, the official said. Cities and towns have until Feb. 11, 2024 to meet the eligibility requirements.

So far, the state has not received any official applications from municipalities hoping to sub into the 10th and final spot, according to the official.

There are, however, four other communities that have already approved home rule petitions seeking the state’s permission to limit fossil fuels in the building sector ahead of the Nov. 10 application deadline: Boston, Somerville, Salem and Northampton.

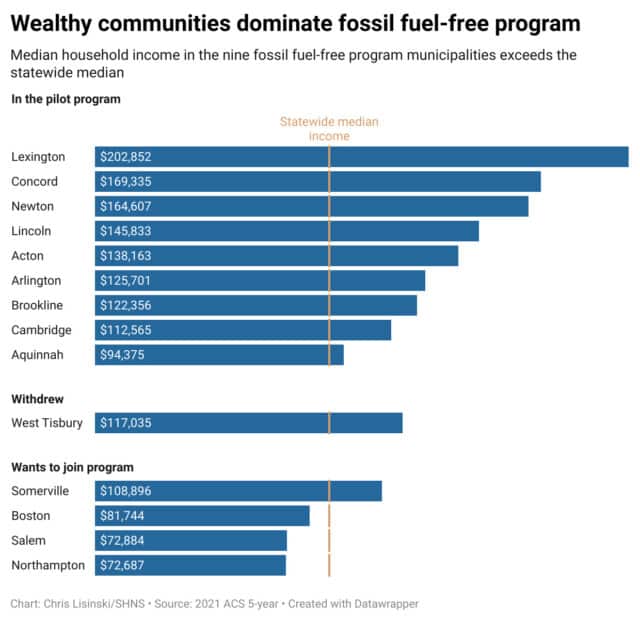

State House News Service graphic

Although only one spot out of 10 is up for grabs, the Healey administration’s decision could transform the program.

Just shy of 400,000 people collectively live in the nine cities and towns already lined up. Boston alone is home to more than 670,000 residents – not to mention some of the most high-profile real estate development in the state – so adding it would more than double the number of Bay Staters who might soon live in communities where fossil fuel use is severely restricted in new buildings and major renovation.

Such a move might boost Healey’s stock among environmental advocates, some of whom have been ramping up pressure on the governor to put action behind her bold climate promises. It could also hand a win to Wu, who already signed an executive order banning fossil fuels in new city-owned buildings but needs state permission to apply similar requirements on other real estate.

In a July 31 interview on WBUR’s “Radio Boston,” Wu said the city’s “hands are tied” on big climate policy goals, including the push to decarbonize buildings.

“We have the resources, the willpower, the partnerships, that are ready to go, and yet we’re still waiting to hear back if we will get into the state’s 10 communities pilot program to be able to fully regulate how we can allow for or phase out fossil fuel infrastructure in buildings,” Wu said. “We’re trying to do everything we can, but without that bit of state legislative approval – or at this point, it’s now on the executive side, executive approval – we can target the biggest buildings, we can try to do our best on some residential spaces where we can provide grants directly, we’re working on public housing, but to be able to do all of it, we can’t get to the whole middle of that without this authorization that we’ve been waiting for.”

“We have to be shifting our timelines decades faster, and that means we need to get started now,” she added.

The Healey administration might also see upside in the other options. Aside from Aquinnah, which is a small Martha’s Vineyard town, every community in the pilot program so far is inside or just adjacent to the Route 128 belt.

“We need to prove to other communities that this is possible, and it’s hard to do that if there’s a lot of similarity between the cities and towns,” said Rep. Lindsay Sabadosa of Northampton, who filed legislation that would expand the program to more than 10 municipalities. “It doesn’t have a lot of geographic diversity, and if you’re going to use this as a pilot to show that this can work for the state, you need to have different sorts of communities involved.”

The current list of participating cities and towns is overwhelmingly wealthy: eight of the nine have six-figure median household incomes. U.S. Census data estimate Somerville’s median household income at about $108,000 in 2021, higher than Massachusetts as a whole, while each of the other three potential substitutes fell below the statewide median.

State House News Service graphic

Lisa Cunningham, co-founder of the ZeroCarbonMA advocacy group, said the current makeup of the program reflects a “really big equity issue.”

“The communities that are not being allowed in are significantly less affluent, have significantly more people of color, have significantly greater health risks and poorer health outcomes,” Cunningham said. “It’s simply inequitable.”

Her group has endorsed the legislation filed by Sabadosa and Northampton Democrat Sen. Jo Comerford (H 3227 / S 2093), which would eliminate the 10-community cap on the program and allow cities and towns to join without formally filing a home rule petition. Participation would still be voluntary, not mandatory in all municipalities.

The proposal faces opposition from some developer groups, which have warned that banning fossil fuels in construction will increase costs and stifle production.

“The whole concept of fossil fuel hookup bans is premature,” Greater Boston Real Estate Board President and CEO told MASSterList, adding, “Are we far enough along with power sources from renewables to be able to actually pull that off?”

Cunningham said she believes more cities and towns than the four expected to compete for one substitute position want to require cleaner energy in new construction or major renovation, but have not taken formal action because their leaders and voters assume the pilot is already full.

“Nobody’s going to take the time to apply to put themselves on a waitlist when there’s no space in the program,” she said.