Developers and designers are vying for the chance to test new models of triple-decker housing on a pair of city-owned parcels in Boston. Pictured are a row of vintage triple-deckers in East Boston, the right-most being recently renovated. Photo by James Sanna | Banker & Tradesman Staff

Architectural avatars of efficient and livable middle-class housing, triple-deckers altered the landscape of Boston and its suburbs in the early 20th century.

Providing attainable housing for working-class immigrants, they also prompted a backlash culminating in the passage of Massachusetts’ Tenement House Act in 1912. Dozens of Boston suburbs from Bedford to Weymouth subsequently adopted the local-option law banning their construction.

Over 100 years later, Massachusetts’ housing affordability crisis is prompting a fresh look at triple-deckers as a solution, not a problem. Changes to land-use regulations in Boston and Somerville could spur construction of a new generation of triple-deckers filling neglected small building lots.

“There’s a lot of good things to say about the triple-decker,” said architect Paul Miller, founder of Neighbor Studio in Cambridge. “They were built at a time when cities really needed affordable housing. They were fast to build, they were affordable for buyers and they provide abundant light and fresh air and usually access to outdoor space.”

The rezoning initiatives are taking place as the Future Deckers Initiative, a partnership between the Boston Society for Architecture and the city of Boston, has provided a fresh set of ideas for designing modern triple-deckers tailored to 21st-century households and contemporary developers’ financial requirements.

Properties at 379 Geneva Ave. in Dorchester and 569 River St. in Mattapan will be awarded to developers by the Mayor’s Office of Housing in 2024 as proving grounds for the new prototypes.

Proposals are due Feb. 14. The request for proposals lists assessed values of $315,000 and $350,000 for the two parcels, respectively, but the city will accept offers as low as $100 in exchange for public benefits such as a sizeable affordable housing component.

The pending disposition follows a 2021 design competition which received nearly two dozen responses from architects and builders, including Miller.

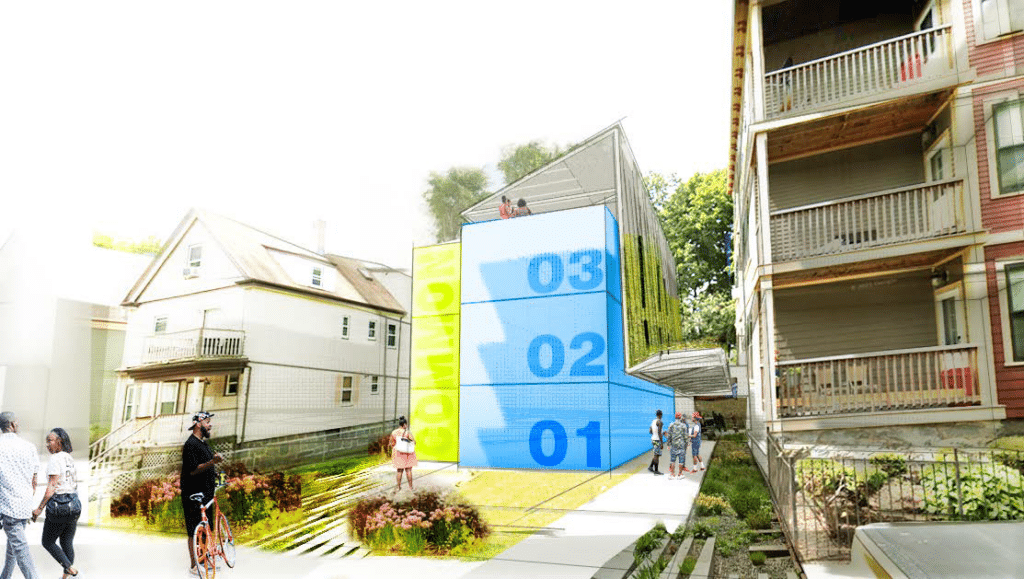

A 2021 city-sponsored design competition to imagine a “future decker” generated nearly two dozen responses, like this sustainability-minded proposal from an eight-person team led by architects and development consultants Ben Bruce, Hakim Cunningham and Olivia Humphrey. Image courtesy of Ben Bruce, Hakim Cunningham and Olivia Humphrey

A Vernacular Form, Updated

Several themes emerged from the responses, said Wandy Pascoal, the BSA’s program manager of housing innovation. Sustainable designs including Passive House and solar systems were common, with the goal of reducing operational costs, along with resilient designs that anticipate sea level rise.

At the same time, respondents sought to preserve triple-deckers advantages over larger multifamily buildings, such as their ample daylight, porches and accessibility to the outdoors.

“There’s been this thread that exists since the inception of the triple-decker in the 1880s where people have these deep relationships with them, and that’s something we want to hold onto,” Pascoal said.

Triple-deckers’ potential to spur infill development on small parcels is a major focus of the Future Deckers Initiative. A 2022 citywide land audit commissioned by the Wu administration identified over 1,200 municipal-owned vacant or underutilized parcels in Boston that could be sold to developers for housing creation, three-quarters of which are 5,000 square feet or smaller.

“True to its name, the Future Deckers Initiative is thinking about a typology that can be efficiently constructed to get at this ‘missing middle’-type building that can be used at infill sites throughout the city,” said Paige Roosa, director of Boston’s Housing Innovation Lab.

Several respondents proposed advanced construction techniques, including prefabricated and modular construction, to shorten project timelines and control costs, Roosa noted.

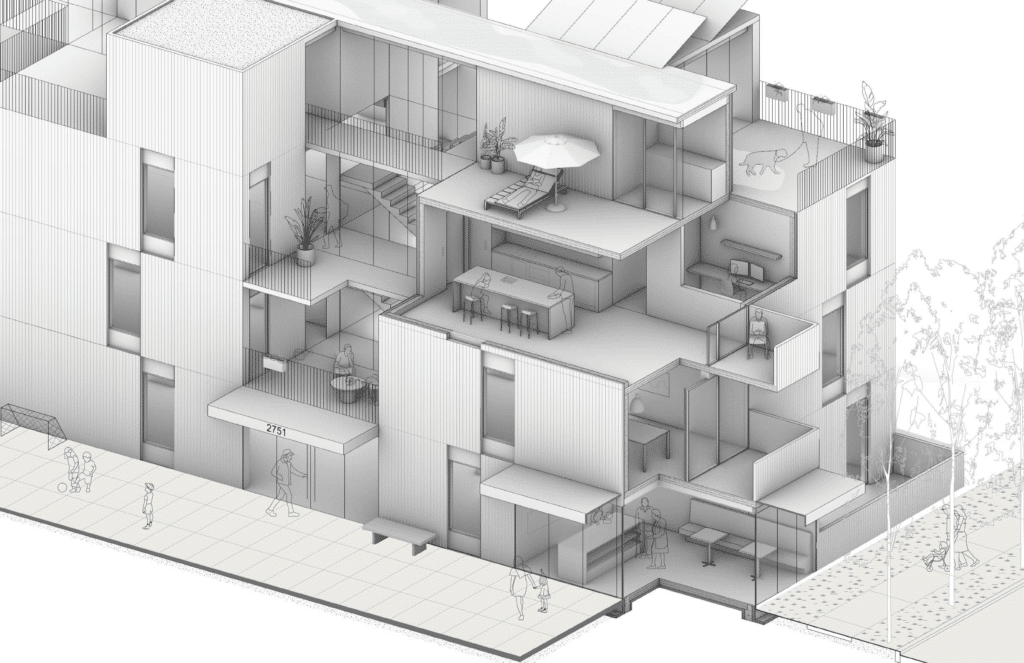

Cambridge architects Neighbor Studio designed a flexible, mass timber-based “future-decker” that is intended to be adapted to a variety of parcel sizes and ground-floor uses. Image courtesy of Neighbor Studio

Cities to Dismantle Zoning Barriers

The Somerville City Council legalized construction of three-family structures citywide by-right in November in order to comply with the MBTA Communities state zoning law, eliminating the need for developers to obtain specific approvals from land-use boards.

But in Boston neighborhoods where triple-deckers are a prevailing housing model, three-family developments still face hurdles. Even if the neighborhood zoning allows three-family dwellings, development is restricted by other factors such as minimum lot sizes, said Joseph Hanley, a partner at Boston-based McDermott, Quilty, Miller & Hanley LLP.

“You’ll see this in Mission Hill where there’s a lot that’s 4,800 square feet and it’s vacant and you want to go in and do a three-family project,” Hanley said. “You still need a variance, because the lot isn’t 5,000 square feet, even though the use is allowed.”

Pending rezoning in Mattapan could expand the ranks of neighborhoods where these homes can be developed.

The Boston Planning & Development Agency’s PLAN: Mattapan rezoning, which is set for final approval by the Boston Zoning Commission on Jan. 10, would create a new base zoning district allowing three-family homes to be built in a triangle of land bounded by Blue Hill Avenue, Morton Street and the MBTA commuter rail’s Fairmount line. The changes reflect the plan’s goal of encouraging moderate-density multifamily development.

And the BPDA’s Squares + Streets initiative will propose a series of “small area plans” in 2024 that rezone areas around transit and major corridors for higher-density housing development.

Steve Adams

New Wrinkles for Building Systems

One wrinkle in the proposal by Neighbor Studio’s Miller is elimination of the basement, which typically housed heating systems, in favor of a frost-protected, shallow foundation. Newer building systems such as mini-split heat pumps eliminate the need for basement utility space, he said, while offering additional benefits in minimizing potential flood damage.

Miller’s design also would test the potential for modular construction using cross-laminated timber to shrink construction schedules and beat traditional construction budgets.

“The real requisition is: Is it going to pencil out?” Miller said. “The priority from the city’s perspective is more housing units above everything else. Our hope is we can prove it costs less than stick-frame construction.”