Publicly-owned properties are a lucrative but challenging real estate frontier in Greater Boston, as developers pursue centrally located sites such as MBTA stations, postal facilities and air rights parcels above the Massachusetts Turnpike.

Now a transit group sees potential to unlock a new category of real estate: 11 MBTA bus yards and garages, including several in neighborhoods already in full-fledged building booms.

A Better City says public-private partnerships could offer mutual benefits to the MBTA and developers. The transit agency would get a source of revenue for a new electric bus fleet by selling development rights above the bus maintenance facilities in Boston, Cambridge, Quincy, Lynn and Medford. Developers would get a chance to build on some prime real estate that’s previously been off-limits.

“It’s no secret that the T has more than a handful of prime urban sites,” said Glen Berkowitz, an author of the study and project manager at A Better City. “Instead of selling them off to the highest bidder and relocating [the bus storage] to the periphery, maybe you can create something at the site that’s multiuse, including a new bus hub.”

The 40-acre Cabot Yards bus yard in South Boston sits next to a stretch of Dorchester Avenue attracting investment by major developers including National Development. Another, the 8-acre Arborway garage, is located in a section of Washington Street where hundreds of new apartments have been built in recent years and is steps from the Orange Line’s Forest Hills station.

“Many of these sites are in the fringe urban areas already being targeted for development,” said Liz Berthelette, research director at Newmark Knight Frank in Boston. “This is where the path of growth has been going: out from the urban core, along rail and transit access.”

The MBTA in 2017 estimated maintenance needs for its eight bus maintenance garages at $808 million but has only allocated $83 million through 2023. At the same time, it’s testing the potential of battery-electric vehicles and hybrid diesel-electric buses. The MBTA activated its first three battery-electric buses on the Silver Line on July 31, kicking off a two-year pilot testing the reliability and costs of a larger zero-emissions fleet.

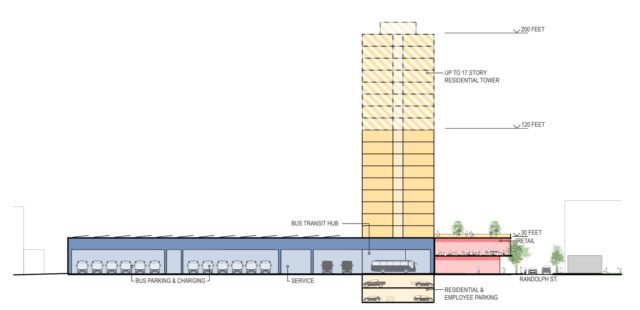

A conceptual design for a commercial real estate development on top of a redeveloped Albany Street MBTA bus garage in Boston’s South End. Image courtesy of A Better City and Jacobs Engineering

Group Inc.

Housing atop South End Garage?

As a case study, ABC focused on the MBTA’s property at 439 Albany St., which sits between National Development’s Ink Block mixed-use development and The Abbey Group’s planned 1.6-million-square-foot Exchange South End office and lab project. The MBTA parcel currently houses a 51,244-square-foot maintenance facility on 5 acres.

The case study contemplates a developer building a 227,000-square-foot residential tower ranging from nine to 17 stories atop a new bus garage with storage and charging equipment for 112 battery-electric vehicles.

Other facilities are located on Southampton Street in South End, Arlington Avenue in Charlestown, Salem Street in Medford, Western Avenue in Lynn, Massachusetts Avenue in North Cambridge, Hancock Street in Quincy and next to the Encore Boston Harbor casino.

“Even for some sites that aren’t in the middle of the urban core, the market has shown a very healthy appetite,” said Brendan Carroll, director of intelligence for Perry Brokerage. “This is the new category that’s the frontier of opportunity. It has everything that you want: it’s generally larger [sites] than you find in the urban footprint, and it’s almost by definition in a great transit location.”

The study did not recommend ownership models, acquisition costs or density bonuses. And high-density development would likely face the same neighborhood opposition as a traditional project, Berkowitz noted. But residents might be more willing to accept development as a tradeoff for quieter, low-emission vehicles, he said.

The design concept remains unproven, with consultant Jacobs Engineering unable to identify any examples of such projects in the U.S.

Plugging in Electric Bus Fleet

The trickiest part of the A Better City proposal: all of the sites would require coordination with state transportation agencies that don’t have a reputation for lightning-fast movement on real estate projects. Attempts to build a tower above South Station stretch back to the 1990s, and still are in preliminary permitting. Boston Properties first began eyeing the parcel next to North Station for a mixed-use development in 2001. The first phase of The Hub on Causeway, a citizenM hotel, opened last week.

Local land-use boards would have the ultimate control over what gets built, adding another potential roadblock.

Given those obstacles, developers would likely need zoning incentives to make the financials work, said Aaron Jodka, director of research for Colliers International in Boston.

Steve Adams

“You’d certainly want some density bonuses,” Jodka said. “It becomes a larger decision with multiple stakeholders. You need the density and floor area ratio to justify the costs, since the report suggested offloading the majority of the replacement of the bus facility to the private developer.”

A Better City’s Berkowitz said the estimated timeline for wider electric-battery fleet adoption could coincide with the length of the disposition process.

“It’s likely the technology will evolve in five to seven years to the point where you can buy a fleet of 100 vehicles,” he said. “The T should get started now to offer up a variety of its sites. It could take as much time to get that permitted facility as it would for the industry to mature and start buying battery-electric buses in large numbers.”