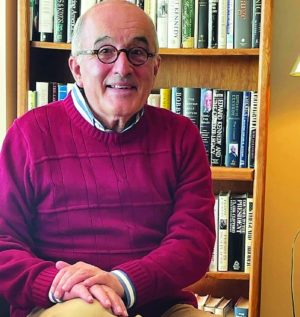

Larry DiCara

Attorney and former Boston city councilor

Age: 73

Photographs of political giants like Ted Kennedy, Tip O’Neill and Joseph Moakley line the walls of former Boston city councilor Larry DiCara’s Jamaica Plain home, representing a growing gallery of departed figures who dominated Bay State and national affairs during the late 20th century. A Dorchester native and graduate of Boston Latin School and Harvard University, DiCara became the youngest person ever to be elected to the Boston City Council in 1972 at the age of 22. He later ran for state treasurer in 1978 and Boston mayor in 1993. Today, DiCara remains active in real estate as an attorney representing landlords and developers before public agencies and neighborhood associations.

DiCara was struck by a car that jumped the curb in Marion in January 2021, after the driver suffered a fatal medical incident. The incident left DiCara in and out of hospitals for nearly five months, during which he underwent several operations to repair arm and foot injuries. DiCara said he’s grateful that he suffered no permanent injuries preventing him from returning to his work schedule, including lunches spent dispensing free advice on Boston politics and real estate.

Q: How does today’s real estate and development climate compare with your days on the City Council?

A: Truth be told, there was not a lot of commercial development in the 1970s. We had four big banks and they all put up new buildings which were permitted by the late 1960s. We had double-digit unemployment, interest rates and inflation throughout a chunk of the 1970s, so there was not a lot of commercial development. Realistically what had happened when the new buildings opened up is the law firms exited the old buildings, and then some of them emptied out. I had a campaign headquarters at 10 Post Office Square – where I later had a law office – and we got it for, like, $100 a month because there was nobody else prepared to pay any rent in the building.

Residential property [values] probably didn’t increase in Boston for the decade. It was flat. We had arson rings, one of which was focused on Symphony Road, and another hit properties all over the city, which is the topic of a recent book, “Burn Boston Burn.” Nobody got hurt, they just liked watching the buildings go up. It included people on the [Boston] Fire Department and the [Boston] Police Department. It was insane. We’re a very different city.

Q: What were the key issues that led to the City Council’s decision to support the Quincy Market redevelopment?

Q: What were the key issues that led to the City Council’s decision to support the Quincy Market redevelopment?

A: It was considered risky. I knew about [marketplace redeveloper] The Rouse Co. because I read a lot about them and they had done two model properties in Maryland and Virginia in the late 1960s. I knew Jim Rouse and he was a blue-chip guy. We had plenty of fly-by-nights appear before the City Council. The interesting story is that no banker or insurance company in Boston wanted to give them a mortgage. It was a lot of money then – I want to say $23 million. The people who worked there [in the wholesale markets], the meat and fish guys, were paying $1 a square foot for rent, and it was traumatic for them. I’m not sure, with how citizen activism has evolved, whether you could do that today.

The end result was it brought vitality to dormant buildings, by creating economic activity on the other side of Congress Street from City Hall. Had Scollay Square not been cleared by the Government Center redevelopment, [Boston Mayor] Kevin White would not have looked out the window and seen the abandoned buildings [at Quincy Market]. When Faneuil Hall was operating, that created pressure to remove the elevated Central Artery. The increase of property taxes on either side of what is now green space has been extraordinary. When the elevated was torn down, people saw how close the Seaport was.

Q: Boston politics has been relatively genteel in recent years compared with the intense personal rivalries and the desegregation era unrest of the 1970s. What was your experience on the City Council like?

A: It was brutal. I was the only member of the Council or the School Committee who did not support the anti-busing movement. I thought the remedy wasn’t really a remedy, but I felt that I should not be standing up and asking someone to oppose a decision of a federal court. The end result is the city emptied out. We lost maybe 10 percent of our population in three or four years. We bottomed out at about 534,000 and we’re currently about 150,000 more. A lot of housing was abandoned and it became available for arson and homeless people.

I came up with a theory that because so many people left so quickly, housing was available for different kinds of people, so the people who moved in did not ask the neighbors which Mass they went to on Sunday or who they were living with and whether they were married: all of the questions that people used to ask in Boston. As a result, neighborhoods like South End and Jamaica Plain were transformed with many different people who are still here. They don’t have kids, for the most part. Between 1930 and 2010, the number of school-aged children living in the city had been reduced by 40 percent. You have fewer people occupying the same real estate. The second floor of the three-decker where there are now two people, we had six.

Q: How did the city of Boston push back against the suburbanization pressures that caused businesses and residents to relocate?

A: People have to feel safe, first of all. When the population declined in the 1970s, many people didn’t feel safe in their own neighborhoods. Number two, people have to be able to afford to live here, and as someone who moved into Jamaica Plain almost 30 years ago, JP doesn’t have a lot of affordable housing. Yuppie Nation comes in and buys a three-decker, the renters leave and they populate it with young people. If we want this to be a city where people raise their children and send them to public schools, as opposed to moving out to the ‘burbs when their oldest child is 4 or 5, the schools have to be better.

Q: What’s your impression of Mayor Michelle Wu’s approach to reforming development, planning and permitting?

A: [Former Boston Redevelopment Authority Director] Ed Logue said if you want me to come to Boston [from New Haven, Connecticut], I want planning tucked into the BRA, and a membership in a private club so I can talk to the people who can get stuff done. I happen to think it worked relatively well. You can make an intelligent argument that planning and development can be hostile to each other. In my decades in law, I’ve seen plenty of zoning and planning boards, and sometimes there’s constructive tension, but I think we’ve had a pretty good track record. When you have a dynamic agency, creative folks are attracted to it. She should be cautious in what she does [with reform] because it requires an act of the legislature. [BPDA Director] Arthur Jemison is a really solid guy. I knew him when he was here before and when he worked in Washington. Everybody says he’s off to a good start.

Q: Does Boston have separate sets of rules for different neighborhoods and how much weight their public comment shapes the development review?

A: Part of the problem is we do not have one set of rules with respect to neighborhood review. There are some neighborhood councils that are elected, such as Jamaica Plain, and others where they’re appointed. If I were doing a deal in my neighborhood, which is called Pondside, I would have to deal with the Pondside Association, the abutters, the neighborhood council – on top of the BPDA and other folks on the City Council. Truth be told, it’s great for lawyers, and maybe that can be streamlined. The civic associations are very powerful and listened to. I think [Wu] is off to a good start. She’s the most cerebral person to be mayor since Kevin White, and maybe ever. She’s wicked smart, as we say in Dorchester, and I hope when she’s done in four or eight or 20 years, the city will be a better-off place than it is today.