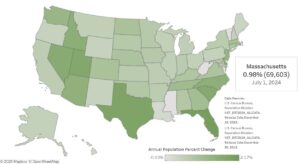

Among the 50 states and D.C., Massachusetts was 13th in population change and 15th in percent population change from July 1, 2023 to July 1, 2024, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Image courtesy of the UMass Donahue Institute

Fueled by the highest immigration levels in decades, Massachusetts saw its largest population increase in 60 years between 2023 and 2024, and the rate of domestic outmigration has significantly slowed, according to U.S Census data released last month.

Between July 1, 2023 and July 1, 2024, the state’s population increased 69,603 from 7,066,568 to 7,136,171 – a increase of just under 1 percent (0.985 percent).

That’s the largest annual percentage increase that Massachusetts has experienced since between 2012 and 2013, according to a UMass Donahue Institute analysis of the December U.S. Census population estimates.

Numbers wise, it’s the largest annual population increase since the end of the “Baby Boom” in 1964.

Those gains made Massachusetts the fastest growing state in New England and the second fastest growing state in the Northeast after New Jersey, according to the institute.

The largest driver: immigration, estimated at 90,217 incoming immigrants between 2023 and 2024. The census estimates that’s the highest immigration level since at least 1990.

“While immigration is the single largest driver of population change in Massachusetts… other factors also play a role,” according to the institute’s analysis. “In 2024, Massachusetts saw more births (67,851) than deaths (61,133), contributing 6,718, on net, to the population growth in Massachusetts.”

Massachusetts has seen an influx of thousands of refugees and migrants seeking asylum from wars, political unrest and environmental disasters, who have sought temporary housing in the state’s emergency family shelter system, straining the physical and financial limits of the system. The census data does not delineate between immigrants legally seeking asylum or refuge and those otherwise entering the country.

Domestic outmigration, the term used to describe people moving out of one state to another state, has been a contentious political topic for the past several years, as many young adults and families left Massachusetts in the early days of the pandemic, settling in states with lower costs of living.

Conservatives point to high taxes as the reason for domestic outmigration, calling on Democrats to lower tax burdens to keep Bay Staters from moving. Progressives, on the other hand, have pointed to high housing and child care costs, and called for more state investment in programs to lower those costs for families.

A report from U-Haul, based on rentals of one-way trailers from one state to another, listed Massachusetts as the second-to-last state in the U.S. in terms of incoming U-Hauls as a way to measure migration. The right-leaning Massachusetts Fiscal Alliance used the report to call for Gov. Maura Healey to make tax cuts.

“The U-Haul report confirms what we all see with our own eyes every day. Our friends, family, and neighbors are leaving our state in record numbers for states that are less hostile to working and living. This is not sustainable and Gov. Healey needs to share with the state a plan for broad based tax cuts and eliminations she will make during her upcoming State of the Commonwealth in order to get our state back on track. If Massachusetts is going to maintain its tax base, we need to do better and the Governor needs to lead,” Paul Craney, a spokesman for the Fiscal Alliance, said in a statement.

The Massachusetts Opportunity Alliance also reacted to the U-Haul report on Monday.

“Massachusetts is a state we’re proud to call home, but rising costs and high taxes are driving residents to seek better value elsewhere,” said Christopher Anderson, president of the Massachusetts High Technology Council, which co-founded the alliance along with the Massachusetts Competitive Partnership and Pioneer Institute. “Our ranking as the second-worst state for one-way U-Haul moves highlights this troubling trend. It’s time to make Massachusetts a place where everyone can afford to thrive.”

The census data shows that outmigration from Massachusetts has significantly slowed over the past two years.

“Domestic migration in Massachusetts has been rebounding since a peak net outflow of 54,843 in 2022, suggesting that the 2021-2022 period migration may have been due to a short-term shock effect, potentially influenced by work-from-home trends or urban-to-rural movement following the COVID-19 pandemic,” the Donahue Institute analysis says.

It continues, “By 2023, net domestic outmigration decreased to 36,572 persons and then decreased again to 27,480 net outmigrants by 2024 – nearly half of the peak outflow in 2022.”

Total migration has been a net positive since 2020, with decreasing out-migration and increasing immigration. In 2021, net migration increased by 1,762; in 2024, that net migration increased by 62,737 people, according to UMass.