Little new development has occurred in the Raymond L. Flynn Marine Park in recent decades because of regulations favoring marine industrial uses and high construction costs.

South Boston’s industrial park could support up to 4.2 million feet of new development if restrictions on marine-dependent commerce are loosened and the park is rezoned for mixed-use projects, according to a two-year study of its economic potential.

Development pressure is growing on the 191-acre Raymond L. Flynn Marine Park as the rest of the waterfront is rapidly built up with office towers, luxury housing and hotels.

“It’s not the no-man’s land it was in recent memory and that’s what is driving this,” said Geoffrey Lewis, a vice president at Colliers Boston. “The market has pushed out and there’s now the demand for the kind of uses they’re trying to encourage in the industrial park.”

But only a handful of projects have been built in the last two decades in the marine park, where more than two-thirds of the area is zoned for marine industrial use. Industrial rents generally don’t support the cost of new construction, the report said, and deteriorating port facilities would require millions in upgrades by developers or public sources to make many of the parcels suitable for marine industry expansion.

“We’ve been very successful finding a mix of tenants in the existing buildings, but there’s still a lot of vacant land out there,” said Richard McGuinness, deputy director of waterfront planning for the Boston Planning and Development Agency. “As these facilities become obsolete, what would be the building prototype we would advocate for?”

One idea suggested by a team of master plan consultants led by Utile Inc.: encouraging the development of high-bay industrial space on the lower levels of new developments, with assembly and office space above. Such “contemporary flex-industrial space” could attract a variety of businesses including biotech, advanced manufacturing and e-commerce, the report said.

Allowing mixed-use projects with a floor area ratio of 4.0 could spur 4.2 million square feet of development, the consultants estimate.

They point to Jamestown’s Innovation and Design Building on Drydock Avenue as a model for the area’s future growth. The Atlanta developer has spent $150 million since 2013 renovating the 1.3-million-square-foot former Army warehouse and adding amenities for its growing roster of office, lab and artisan tenants.

Another nearby property, the 350,000-square-foot 12 Channel St., is leased to more than 20 manufacturing and office tenants, including a new shared working space for the nonprofit MassRobotics that opened in February. Developer Related Beal has indicated it wants to bring more R&D tenants to the 286,000-square-foot 27 Drydock Ave., which it leased in December.

“We look to those as the gold standard,” McGuinness said. Tech and R&D “can co-exist with the more gritty uses in the park, but they also pay a higher rent, which could help underwrite the construction of a new building.”

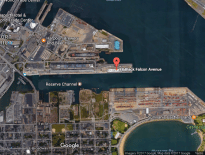

And on Friday, Boston-based Davis Cos. paid $60 million to buy the ground lease for the 376,000-square-foot 88 Black Falcon Ave. It’s hired Boston-based architects Dyer Brown to update the mixed office and industrial complex. 88 Black Falcon Ave. is currently 94 percent occupied by office and industrial tenants, including recent arrival Optimus Ride, an autonomous vehicle startup that occupies 19,000 square feet.

A New Home For ‘Airport-Dependent’ Companies?

The entire park at the eastern end of the Seaport District is owned by the BPDA’s sister agency – the Economic Development Corp. of Boston – and Massport, which typically sign ground leases with developers for existing buildings and new development.

Massport real estate officials are in negotiations with two developers who responded to a 2016 request for proposals for its marine terminal property on Fid Kennedy Avenue. The agency in December selected Cape Cod Shellfish & Seafood and Pilot Development Partners as developers for two parcels.

With more seafood and perishables arriving in Boston via Logan International Airport, the report suggests allowing more “airport-dependent” uses in the marine park where goods could be processed.

“One of the greatest assets for the park is its proximity to Logan, the Conley shipping terminal and interstate highway system,” the BPDA’s McGuinness said.

But the economics may not be attractive to industrial tenants, said Austin Smith, a senior vice president with Colliers Boston who is representing a client scouting locations for a commissary in the city. The cost of truck tolls in the Ted Williams Tunnel for the trip from the airport to South Boston could be prohibitive, he said.

Smith was more optimistic about the prospects for manufacturing uses generated by the life science industry.

“There’s a pattern of those guys coming (from Cambridge) and occupying space in the Seaport, and we’d all like to see that,” he said. “Often that industry has a level of test manufacturing which gets us a little towards the industrial base that we all value in the city.”

The BPDA will host office hours on April 4 from 9-11 a.m. and 4-6 p.m. and on April 12 from 5-7 p.m. at 22 Drydock Ave. The proposed changes are expected to be reviewed by the BPDA board of directors on May 11, followed by submission to Secretary of Environmental Affairs Matthew Beaton for final approval.

This story was updated to include the Davis Cos.’ purchase of the ground lease at 88 Black Falcon Ave. on Friday after Banker & Tradesman’s print edition went to press.

|

|