The resurgent debate over the North-South Rail Link has been framed mostly in terms of its potential transportation benefits, but the stakes are high for real estate development in Boston as well.

Building a rail tunnel linking North and South stations would open up new development sites behind both transit hubs, already the focus of large mixed-use projects. It could remove Widett Circle from the running as new rail layover yard location that’s part of the separate South Station expansion proposal, while serving up Widett as a prime parcel for a mixed-use development estimated at $8 billion. It also could eliminate the need to spend over $1 billion on upfront infrastructure costs at Widett Circle.

“Widett Circle has been an eye-opener,” said Brad Bellows, a Cambridge architect who’s been involved with the rail link studies since the 1990s. “This got on peoples’ radar during the Olympic process. When the Olympics imploded, one of the key things that remained was what could happen with Widett Circle.”

Some of the region’s top developers have lined up in support of the North-South Rail Link. Former Related Beal President Robert Beal and HYM Investments’ Thomas O’Brien are on board. Political support is growing, with a majority of the Boston city council now favoring the plan.

Some of the region’s top developers have lined up in support of the North-South Rail Link. Former Related Beal President Robert Beal and HYM Investments’ Thomas O’Brien are on board. Political support is growing, with a majority of the Boston city council now favoring the plan.

But Gov. Charlie Baker has voiced skepticism, with the rail link competing with maintenance costs to fix the ailing MBTA system and major expansion projects such as the $2.3 billion Green Line Extension and $3.4 billion South Coast Rail.

And then there’s the political baggage associated with the memory of the Central Artery Tunnel project and its massive cost overruns.

“For those of you out there who are already thinking this could be the Big Dig, this will be entirely different,” said U.S. Rep. Seth Moulton, making the case to business and political leaders at a New England Council meeting last week.

Moulton says the rail link will upgrade commuting options throughout New England, including connecting his North Shore constituents with growing job centers such as the Seaport District.

“Everybody coming into that new GE (headquarters) facility, they’re not looking at houses north and northwest of the city because it’s impossible to get there,” Moulton said.

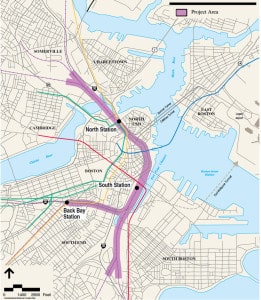

An underground connection between North and South Stations was originally included as part of the Big Dig plans, but eliminated during the Reagan administration. The 2.8-mile tunnel route would dip below-grade south of Widett Circle, travel 1.2 miles beneath the Central Artery Tunnel through downtown and emerge in the MBTA commuter rail maintenance facility in East Somerville.

The administration of Gov. William Weld – another current supporter – took the rail link out of mothballs in 1995, but Gov. Mitt Romney killed the project in 2003 after the cost estimate was updated at $8 billion.

Supporters say recent advances in tunnel-boring technology would reduce the present-day cost to as low as $2.7 billion. The Massachusetts Department of Transportation is putting together a scope of work for a $2 million, eight-month feasibility study that will update cost estimates, spokeswoman Jacquelyn Goddard said.

Widett Circle: Rail Yard Or $8B Development?

Boston’s abortive Olympic bid in 2015 shined the spotlight on the 83-acre Widett Circle industrial area in South Boston as a proposed Olympic Stadium site, to be converted into a mixed-use development after the 2024 games. The Olympic proposal recommended giving developers tax breaks to offset an estimated $1.2 billion in upfront infrastructure costs, including construction of an elevated deck above the MBTA tracks on the property.

The 2.8-mile North-South Rail Link would improve capacity on the MBTA commuter rail while freeing up valuable land near downtown Boston currently used for rail storage, supporters argue.

The North-South Rail Link has two benefits for Widett Circle’s future development potential, supporters argue.

In contrast to the proposed South Station expansion plan – which would add seven tracks and four platforms to upgrade rail capacity by more than 30 trains – the North-South Link would eliminate the need for a midday layover facility in Boston. Widett Circle is one of Massachusetts Department of Transportation’s potential locations for the layover, along with the Beacon Park yards in Allston and a site near Readville Station. With trains continuing through the city, the layover site would shift to a location past North Station.

Widett Circle, currently home to New Boston Food Mart wholesalers, would be available for redevelopment. And because trains would enter the new tunnel south of Widett Circle, an elevated deck wouldn’t be needed.

Pursuing the North-South Rail Link could offer more certainty than the South Station Expansion, which is contingent upon the U.S. Postal Service finding a new site to relocate its massive facility on Fort Point Channel.

“Certainly the post office has talked about the possibility (of moving), but nobody has really been able to tie them down,” said David Begelfer, CEO of NAIOP-Massachusetts. “The post office works at a more glacial speed than we’re looking at planning for the future of the city.”

Behind Rail Hubs, New Potential Development Sites

The rail link also would free up space currently occupied by tracks behind North and South stations for future development. The stations are already magnets for developers, with Houston-based Hines filing updated plans this year for a 2.5-million-square-foot air rights development at South Station.

Next to North Station, AvalonBay Communities is nearing completion of a 38-story apartment tower.

Boston Properties and Delaware North Cos. have started the first phase of their billion-dollar North Station redevelopment, turning a surface parking lot in front of the TD Garden into offices, retail, a movie theater, hotel and high-rise residential.

But another opportunity awaits behind the sports arena, where 12 tracks dead-end at the back of the station to serve five commuter rail lines and Amtrak Downeaster service. Eliminating the vast majority of those tracks could open up another 5-acre development site.

The rail link also could change the way companies approach their real estate site searches in Boston, without having to narrow down their choices to convenience either North or South Shore commuters.

“That makes a difference to employers,” said Aaron Jodka, director of research at Colliers International Boston. “We do feasibility analyses where we’re looking at where employees are coming in from, and that can be an integral consideration when choosing real estate.”

Skeptics Question Costs, Priorities

Some developers remain wary of the costs and how the rail link fits into a lengthening public transportation wish list, including upgrades to the Silver Line capacity and a new diesel multiple-unit train running between Back Bay and the Boston Convention & Exhibition Center. That line would run past National Development’s Ink Block mixed-use development in the South End.

“I’m not enthusiastic about either the (rail link) price tag or the impact of ripping up the city,” National Development’s Ted Tye said via email.

The state needs to set clearer transportation goals, said Greg Bialecki, a former state housing and economic development secretary and partner at Boston-based developer Redgate.

“We have a growing list of these billion-dollar projects that are just in a holding pattern,” Bialecki said. “Do we have the political will to make these big investments? It’s a sign of where we are that we don’t really have a system for deciding (transportation priorities), where we see various elected officials teaming up and becoming advocates for these projects.”

|

|