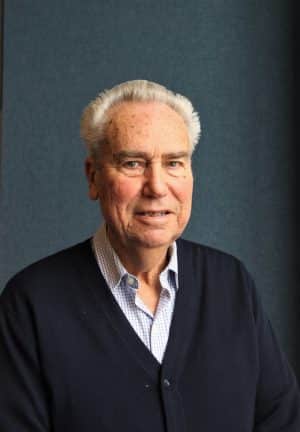

Frederick Salvucci

Senior lecturer, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Center for Transportation & Logistics

Age: 82

Fred Salvucci has always thought big when it comes to transportation projects and how they could shape the Massachusetts economy. A Brighton native, Salvucci graduated from Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1962 and joined the Boston Redevelopment Agency as a transportation planner. Under Boston Mayor Kevin White in the 1970s, Salvucci began to advocate for replacing Boston’s elevated Central Artery with a highway tunnel. Appointed as Gov. Michael Dukakis’ transportation secretary from 1975 to 1978 and 1983 to 1990, Salvucci led the planning for what would become known as the Big Dig, one of America’s biggest public works projects. Salvucci’s current wish list of public works projects includes the removal of another hulking elevated structure: Somerville’s McGrath Highway. And he continues to shape the thinking of the next generation of transportation engineers as a part-time lecturer at MIT.

Q: What influenced your transportation philosophy and the role of public transit versus highway infrastructure?

A: I grew up in Brighton and the [Massachusetts] Turnpike Authority built the turnpike through North Brighton and took my grandmother’s house by eminent domain, and treated everybody in the neighborhood outrageously badly. It made a big impression on me. People should be treated fairly, especially when a public agency is taking action. There’s no excuse for that. Equity and reasonable treatment of people is paramount.

Public transportation allows greater density than you can reasonably achieve with the automobile. Given the way our cities have developed with a lot of suburban areas that are difficult to access by public transportation, it’s really necessary to think about a mix of the two. But beyond a certain point, if you want more economic growth at the margins, the growth has to be handled by public transportation.

There’s been research about the agglomeration of these benefits. I think they’re real. Public transportation, and more particularly rail transportation, is really essential. The environmental impacts of the automobile and sprawl are bad, and it’s not going to get solved with battery electric cars. Do you want more child labor in Bolivia and more dependence on China for the batteries?

Q: When was the idea of depressing the artery first envisioned?

Q: When was the idea of depressing the artery first envisioned?

A: Bill Reynolds was a highway contractor who was 10 years older than me, an MIT graduate and a really interesting guy. We were disagreeing all the time over whether to build the Inner Belt and the Southwest Expressway. We met through Allen Altschuler’s Boston Transportation Review. Because I’d worked for the BRA, we said, “Wouldn’t it be nice if this darn thing were underground?” but it was kind of an idle thought. Reynolds said, “We should do this. This is silly. Let’s fix it.” It was really his idea, but I caught the bug and I’m glad.

Q: Who was the most difficult obstacle to the project from a political standpoint?

A: The biggest opposition came from within the city government when I worked for Kevin White. Kevin was an enthusiastic supporter, but Bob Kenney who was head of the BRA at the time was afraid the construction disruption would slow investment downtown. There were some interests within the downtown business community that had the same disruption concerns [such as] Norman Leventhal from the Artery Business Committee. His initial instinct was to keep an eye on me because he thought I was a little nuts. Once he understood the project, he caught the bug. Thank God he did, because when Gov. Dukakis left office in 1991 and I left with him, the strong base of support in the business community that Leventhal built was maybe the decisive factor in convincing [Gov.] Bill Weld to continue with the project.

Q: Where were the failures that led to the project’s massive cost escalation?

A: There were two primary things. Up until 1991, the federal government would reimburse 90 percent of the actual cost of completion. Had that law remained in place, the feds would have paid for 90 percent and it would not have been a problem for Massachusetts at all. By 1991, Massachusetts was really the only state with a large amount of money at stake, and then the Bush administration changed the rules and any cost increases beyond 1991 were at the risk of the state.

The second thing was the state paused the Central Artery part of the project for two years to reconsider the river crossing: the “Scheme Z” controversy. They admitted the changes cost an additional billion dollars and that was probably an underestimate. All of those curved ramps under North Station where motorcycle riders have died in accidents because of the bad curves and bad sightlines, those weren’t in the original Scheme Z. It was a better transportation design and at least a billion dollars less expensive.

Q: What are the key transportation issues that need to be considered in the future of Widett Circle [24 acres of which the T is hoping to buy for a commuter rail layover yard]?

A: Transportation optimization needs to be the priority there. It’s possible to have economic development on top of it. They’ve got to get the rail right. You’ve got what should be the two-tracking of the South Coast Rail that needs to get through there, you’ve got access to the Red Line maintenance facility, and the two-track Fairmount branch runs through the edge of it. It’s very close to South Station, so it’s an ideal place to have midday storage, although midday storage is an anachronistic idea. The progression to regional rail as opposed to commuter rail calls for much more service in the midday and nights and weekends.

Q: What are your top priorities for transportation projects that you’d like the Healey-Driscoll administration should pursue?

A: Priority is a funny word, because sometimes people think in an abstract way. These things take so long to develop and there are many initiatives that make sense. To me, what Governor-elect [Maura] Healey has to look at is what has been talked about and planned long enough that we can get into implementation reasonably quickly. That includes the Blue-to-Red Line connector, and improving the frequency of the [MBTA commuter rail] Fairmount branch. The rail there isn’t being used adequately. You have big gaps in Dorchester and Mattapan, and there’s track right there. That’s ready to do. The Green Line Extension got short-changed a bit, and there are still people advocating extending it beyond Tufts to Route 16 which I think makes sense. But for me the priority is to tear down the elevated McGrath Highway. You’ve got this incredible new access created by the Green Line Extension, and what should be absolutely stunning development sites have this stupid elevated in the way. Tear the damn thing down and elevate those parcels. There’s so much space there that could be jobs and affordable housing.