Developers of properties such as 15 Necco in the Seaport District are coordinating plans for resilience strategies with the city of Boston, which is planning to build a 6-foot-high berm along the east side of Fort Point Channel. Image courtesy of Elkus Manfredi Architects

With potential for massive property damage in Boston neighborhoods in the path of rising seas, the city is studying funding mechanisms to pick up the multi-billion-dollar tab in coming decades.

A study commission next year is expected to recommend spreading the costs broadly among property owners in coastal neighborhoods, possibly through a district improvement financing mechanism.

“The city is going to have to figure out how to approach this, and what conditions require private property owners to pay,” said Bud Ris, a member of the Boston Green Ribbon Commision which is studying resilience funding models.

Shore-based defenses such as elevating sea walls, building earthen berms and installing absorbent, planted shorelines could cost up to $1 billion in the Seaport District and South Boston alone, according to the Climate Ready Boston study, based upon a projected 40-inch rise in sea levels by 2070.

Convincing private developers to pitch in for flood defenses beyond their property lines might not be a hard sell after recent years’ storms that have landed Boston’s climate vulnerability in the national headlines.

Following a decade of torrid development in the Seaport, property owners and potential future investors are becoming wary of the financial risks posed by climate change, said Brian Swett, Boston office leader for consultants Arup.

“A lot of investors buying existing assets have questions about when market perception of increasing risk is likely to occur,” Swett said. “The question is less about then the event is likely to hit, but during their investment period, what is the climate risk perception in the market? What is the potential reduction in value in seven or 10 years? We’re at the tip of the iceberg in this regard.”

Seaport Developers Already Coordinating Plans

Before the city imposes any mandatory requirements, the new owners of two major commercial development sites bordering Fort Point Channel are planning to voluntarily incorporate resiliency strategies, such as elevating open space and ground floors above future projected flood levels.

Related Beal has notified the city it will propose 1.1 million square feet of commercial and multifamily space on a 6-acre parking lot it bought from Procter & Gamble this year. National Development and Alexandria are proposing a 12-story office and lab building on the site previously planned as General Electric’s new headquarters.

And Procter & Gamble is studying a redevelopment of its adjacent 34-acre Gillette World Shaving Headquarters campus, which borders the parcel it sold to Related Beal.

Up until recently, private developers have been reluctant to pay for resilience measures even on their own properties because many have investment timelines as short as seven years

It’s expected that all three property owners will coordinate site designs with the city’s plan to build a 6-foot-tall earthen berm on the east side of the channel, which is expected to cost up to $20 million, said Richard McGuinness, deputy director of waterfront planning for the Boston Planning and Development Agency.

“The timing is perfect here,” McGuinness said. “We have National Development wanting to move quickly and Related Beal purchasing the 6-acre site from Gillette, which wasn’t something that we thought was going to happen a year-and-a-half ago. We’ll have four years to design, permit and construct the berm, which is about the same as the project schedule for those buildings.”

The Climate Ready South Boston plan lists the Fort Point berm as one of the near-term actions that should be completed by 2025. Properties inland of the development sites have suffered some of the most severe flooding in recent years’ coastal storms, so the berm will offer protections beyond the development sites, McGuinness said.

The city of Boston has committed $1 million toward the berm and is seeking a FEMA grant for another $10 million.

Boston officials have outlined a $1 billion basket of projects to flood-proof the city’s neighborhoods, but face dramatically different challenges funding them in largely working-class neighborhoods like East Boston. Image courtesy of the BPDA

Savings for a Rainy Day

But with long-term resilience costs in South Boston and the Seaport District estimated at $1 billion, a combination of public funding and new private commitments will be needed to pay for a variety of defenses from Seaport Boulevard to Moakley Park.

The Green Ribbon Commission has been studying a variety of district-wide financing strategies to spread the costs fairly, Ris said. One potential model is a business improvement district, similar to the one recently enacted to maintain the Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Greenway, consisting of assessments on owners of properties within a specific area.

Steve Adams

A more effective model could be district improvement financing, which sets aside a portion of future tax revenues from a specific area to support bond payments for resilience projects, Ris said.

Up until recently, private developers have been reluctant to pay for resilience measures even on their own properties because many have investment timelines as short as seven years, Arup’s Swett said.

“From a public policy perspective, it shouldn’t matter what the hold period is for the initial owner. It should be for the entire useful life of the property,” he said.

And strategies to protect individual properties are less effect than neighborhood-wide engineering solutions, Swett said, pointing to the need for collective investments such as a BID or district improvement financing.

“It’s the same way that [condominium] associations handle major projects such as roof replacements. You’re collecting money for those every year and putting it in reserve,” Swett said.

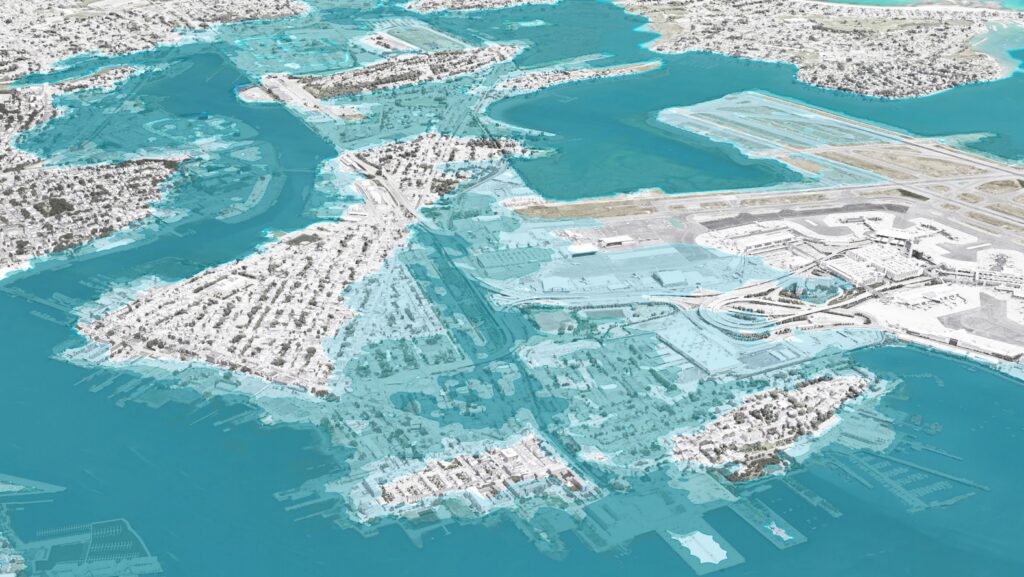

With sea levels forecast to rise between 9 inches and 36 inches thanks to climate change, a severe storm could put substantial portions of Boston underwater by 2030 (dark blue), and even more by 2070 (light blue). Image courtesy of the BPDA

In Working-Class Areas, Who Pays?

Equity is another consideration given the contrasts in the real estate markets between neighborhoods such as the Seaport District, home to global corporate headquarters and luxury condos, and East Boston, a largely residential, working-class enclave.

In East Boston, near-term recommended strategies include installing a 7-foot-tall deployable flood wall across the East Boston Greenway under Summer Street at an estimated cost of $100,000, elevating the Greenway entrance and Massport-owned Piers Park II property, elevating the Boston Harborwalk between the Clippership Wharf development and 99 Summer St., and a deployable flood wall across Lewis Street.

“There is a fairness issue,” the Green Ribbon Commission’s Ris said. “In the Seaport District, these property owners can afford it. In other parts of the city such as Charlestown and East Boston, it’s a big burden.”

|

|