Potential warning flags cropping up in the auto finance market nationwide are prompting state regulators to take a closer look at auto financing here in Massachusetts.

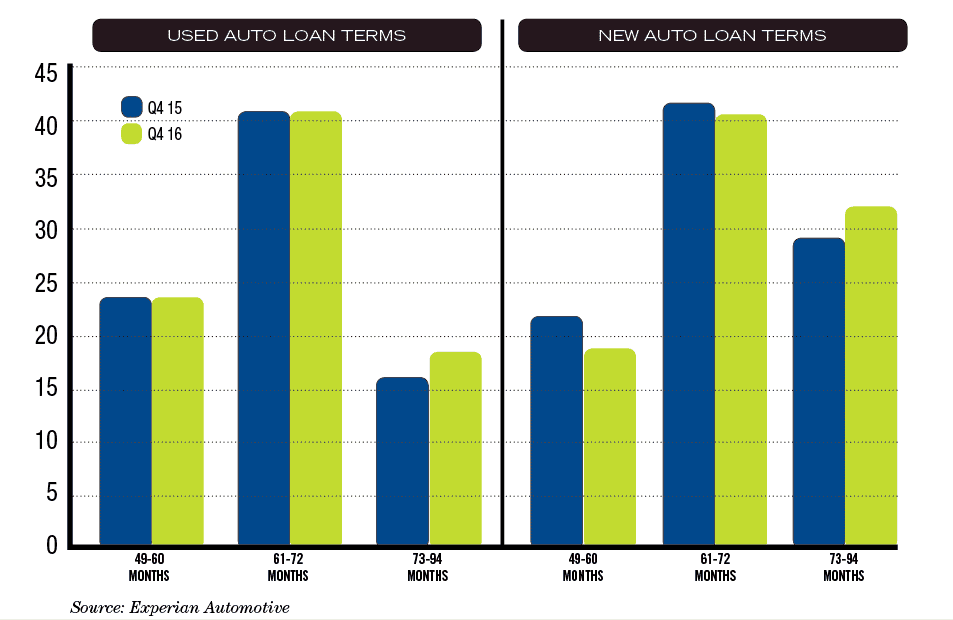

Auto loan balances climbed by $22 billion in the fourth quarter and delinquencies crept upward. Average loan amounts climbed to $30,000 for new vehicles and $19,000 for used, and loan terms also increased. Loans with terms between 72 and 84 months increased to 32 percent of market share from 29 percent in 2015, and the average loan for a new vehicle climbed to 68 months.

Experian, which defines scores under 600 as either subprime or deep subprime, said recently that loan balances in those categories had risen 8.62 percent and 14.57 percent, respectively, on a year-over-year basis. Though prime and super-prime borrowers still capture over half the market, those kind of trends are bound to pique a regulator’s attention.

Here in Massachusetts, the Office of Consumer Affairs and Business Regulation took notice of some of those national trends and decided to check in with the industry locally, said Undersecretary John C. Chapman.

“Subprime” itself isn’t a dirty word, but regulators were concerned about predatory subprime lending practices, particularly at buy-here, pay-here (BHPH) dealerships in and around the state’s Gateway Cities.

Ultimately, the state’s Division of Banks partnered with the Division of Professional Licensure to conduct a review of more than 100 BHPH dealerships. They checked for lemon law violations, reviewed sales contracts and financing records, and looked for potential unfair and deceptive trade practices.

Ultimately, the state’s Division of Banks partnered with the Division of Professional Licensure to conduct a review of more than 100 BHPH dealerships. They checked for lemon law violations, reviewed sales contracts and financing records, and looked for potential unfair and deceptive trade practices.

While regulators said they found a handful of minor, one-off violations here and there, they uncovered no rampant abuses at Massachusetts auto dealerships. The OCABR was pleased – the law is working, people are obeying it – but Chapman said the effort wasn’t about making a giant bust in the first place. State regulators wanted the industry to know that they’re paying attention.

“We see these trends nationally and we just wanted to check in with the industry here in the state,” he said. “A large part of any enforcement organization is just to demonstrate to the industry that we’re out there and we’re looking at this. When people know that they often come into compliance and do the right thing.”

Causes For Concern

Regulators did not consider banks or credit unions in this initiative. Banking Commissioner Terence McGinnis said that the division considers BHPH dealerships to be a higher risk because they may have a greater tendency to miscalculate interest rates, which are capped at 21 percent for motor vehicle loans. Additionally, banks and credit unions are already subject to more stringent rules and regulations.

But lenders big and small have been getting out of the auto business lately. Banks captured 32.9 percent of the market last year, according to Experian, down from 35.6 percent in 2015 (though they still boasted a greater market share than any other lender categories). Credit unions, meanwhile, increased their market share year-over-year to 19.1 percent from 18 percent in 2015.

Giant banks, like Wells Fargo and Santander Consumer, posted declines in auto originations last year and cited their reluctance to make 84-month loans or ease ability to pay standards. Locally, some banks – including Belmont Savings Bank and Brookline Bancorp – have wound down their indirect auto lending business, claiming market conditions as the reason.

Rob Ashbaugh, a senior risk management consultant at the financial analysis firm Sageworks, said that banks get into and out of auto lending, both direct and indirect, for strategic reasons, largely to increase yield. Or in other words, “They love it until they don’t anymore.”

As banks step away from subprime auto finance, that potentially opens up opportunity for those BHPH dealerships. While the industry in Massachusetts is, on the whole, compliant with strong consumer protection laws, the same cannot be said on a nationwide basis. BHPH dealerships elsewhere are frequently characterized by above book-value vehicle prices, interest rates reaching into the 30s and higher repossession rates than other types of dealerships and financiers.

Increasingly, they have another tool at their disposal: starter disrupters, or GPS-enabled devices that allow the lender to effectively repossess the vehicle (by shutting it off) if the borrower misses a payment. Massachusetts treats these devices the same as it would a foreclosure: requiring lenders to provide notice and additional time to make up the payment, McGinnis said, adding, “We look at this intuitively as a foreclosure process.”