There are certainly worse problems to have than a lack of loan losses, but a perfectly performing loan portfolio can actually pose some difficulties when accounting for potential losses – more so if your bank is trying to break into a specialty lending line in an effort to stand out from the crowd.

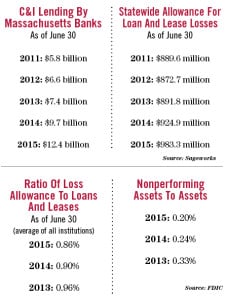

Much ink has been spilled about the boom in commercial real estate lending, and C&I lending has also taken off at many Massachusetts banks. As of June 30, commercial and industrial loans made by Massachusetts-headquartered banks totaled about $12.4 billion, about 28 percent higher than the $9.7 billion booked by that time a year ago, which in turn, marked a 30 percent increase over $7.4 billion at the same time in 2013, according to federal call report data compiled for Banker & Tradesman by the financial analysis firm Sageworks.

While banks don’t necessarily break out the numbers for niche lending lines, Neil Berdiev, a former commercial banker who founded DNB Advisory, said that he’s seen increasing interest among bankers interested in branching out into a particular specialty. That could be mean financing anything from taxi medallions to solar farms to seafood.

“One of the reasons I think banks are exploring potentially entering specialties, especially right now, is the competitive landscape,” he said. “It’s another way to differentiate yourself.”

But in addition to developing credit policies and training staff to handle a particular industry that may be booming in their market area, banks also have to contend with accounting for losses on that particular category of loans.

“With loan growth being an all-time high, we see a lot of institutions servicing different industries or niche industries by default, in a sense,” said Garrett Morris, director of Sageworks’ client services group. “But without a doubt, focusing on a certain industry, or a booming industry in a certain institution’s area, drives the need to perform good risk management practices.”

In the absence of in-house historical loan loss data, he said, bankers can rely on federal call report data, using call codes to create their own “peer groups” by institution size, market area or risk management or lending practices.

“If you don’t have any loss because it’s a new area, you’re trying to more or less peg your loss and produce your loss when you haven’t experienced losses,” Morris said. “Your regulators and external auditors are going to ask for the data points that are telling you to allocate reserves to this specific product or pool and if you don’t have it, that’s not a good thing.”

Moreover, banks might run into the same problem with a particularly successful category of loans. In other words, if banks have been lending to the same product type for years, but have never experienced any losses, then how do they properly account for potential losses? Historical loss data, even culled from peer groups, is only one piece of the puzzle.

Moreover, banks might run into the same problem with a particularly successful category of loans. In other words, if banks have been lending to the same product type for years, but have never experienced any losses, then how do they properly account for potential losses? Historical loss data, even culled from peer groups, is only one piece of the puzzle.

“Historical losses are the starting point, but in themselves, they’re not sufficient,” said Jim McGough, senior audit manager at Wolf & Co.

That’s when qualitative considerations come into play, he said.

“That might be the nature of the loan, what you know about the underwriting of the loans, local economic factors,” McGough said. “These are all the more judgment-based adjustments, and it will be based more on qualitative factors if you don’t have any loss experience. It might be that it’s a very low-risk loan type, too.”

Now For Some New Rules

But new Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) rules expected later this year could throw a monkey wrench into this model. Until now, banks have focused on calculating loan loss reserves using what’s called the “incurred loss model.” Although FASB is still finalizing the new rules, financial institutions will eventually have to start calculating their loan loss reserves using what’s called the “current expected credit loss” (CECL) model.

“The expected loss model is different. You’re asking yourself, ‘What losses are going to occur on all my financial assets on all my loans over the life of the loans?’ And that’s a very different calculation,” McGough said. “It’s a much lower threshold for recognition of impairment allowance because a loss does not have to be probable.”

That will mean the historical period used to calculate loan loss percentages will increase in length, but moreover, the new rules could pose particular challenges for the qualitative analysis used to calculate loan loss allowances, Morris said.

“It’s almost like you’re becoming an economist,” he said. Predictions for what “the future hold for that product, that market, is going to be required, we think, for the CECL calculation and that’s going to be really tough to do for qualitative analysis,” he said. “It’s already difficult, but they’re just adding an even greater level of difficulty to that portion of the analysis.”

|

|