Credit report data including credit scores, debt collection rates and other measures of financial health reveals large disparities and vast economic imbalances between different neighborhoods in Boston and cities in Massachusetts.

That was one of the overarching themes in a recent report from the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston that examines credit conditions in cities across Massachusetts, from Springfield to Newton, as well as in Boston neighborhoods from Roxbury to Beacon Hill. This is the first time the Boston Fed has conducted such a report.

Called “The Concentration of Financial Disadvantage: Debt Conditions and Credit Report Data in Massachusetts Cities and Boston Neighborhoods,” the report is based on data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and Equifax that represents a 5 percent sample size of all U.S. citizens with credit reports.

“This wasn’t a cheery paper to read because of the levels of concentration and the differences,” Prabal Chakrabarti, senior vice president and community affairs officer at the Boston Fed, told Banker & Tradesman. “I wasn’t surprised, but I am not pleased.”

Half of consumers in Springfield, Lawrence and the Boston neighborhoods of Roxbury and Mattapan have subprime credit scores (less than 660), compared to just 8 percent in Newton and the Beacon Hill neighborhood, according to the report.

About one in three residents of Roxbury and Mattapan have debt collections on their credit reports, compared to just 5 percent in several higher-income Boston neighborhoods.

Chakrabarti said the Fed did this report to offer another lens into a community’s economic conditions, and because of the major role credit scores and debt levels play in a person’s access to banking, affordable housing and the cost of borrowing cash.

“The advent of online credit offerings on your phone and computer have replaced credit card mailings and have been even more ubiquitous,” said Lawrence Andrews, president and CEO of Massachusetts Growth Capital Corp. “It has become a real issue for small business owners obtaining credit online from non-bank lenders and then paying upwards of 25 to 40 percent with fees (60 percent plus), and it is truly unregulated. It continues the cycle of poverty and working poor.”

Similarities and Differences

While there were large disparities, Chakrabarti acknowledged that some of the debt level differences were not as stark as he initially thought.

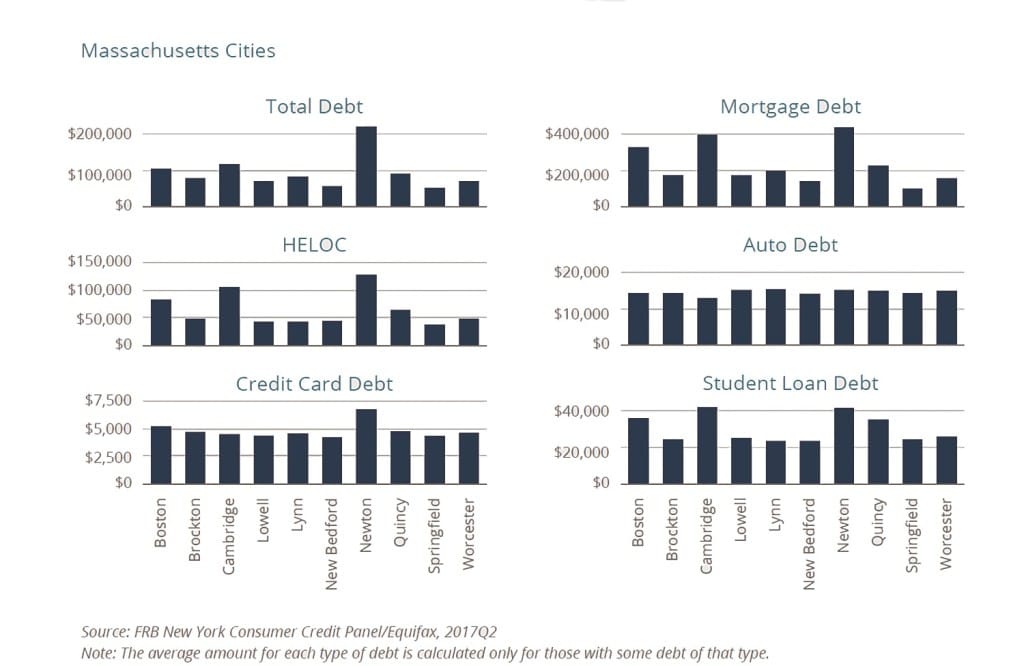

For instance, average credit card and auto loan debt amounts in the cities of Boston, Brockton, Cambridge, Lowell, Lynn, New Bedford, Newton, Quincy, Springfield and Worcester were all similar.

But the piece missing behind that data, according to Chakrabarti, is the cost of the credit and the value of the asset the debt is based on.

When it comes to the auto data, there is something to be said about the number of people in wealthier communities that can pay for cars in cash, said Chakrabarti, as well as access to public transportation – only 14 percent of those in Cambridge had cars, compared to 31 percent in Lowell.

Furthermore, Chakrabarti added, debt levels are really driven by assets.

While some debt levels are similar, there were wide disparities in mortgage and home equity line of credit debt levels.

For instance, mortgage debt in Cambridge and Newton was roughly $411,000 and $444,000 respectively, compared to mortgage debt in Springfield and New Bedford of roughly $111,000 and $150,000 respectively.

The major differences in the report were most transparent in credit scores and debt levels.

Not only do those show that there are large pockets of the population living month to month, but also the level of inequality within the different neighborhoods in Boston and the different communities of Massachusetts.

In Roxbury, 22 percent of those with a credit score have at least one account that is more than 60 days past due. In the South Boston Waterfront, Beacon Hill, the Leather District and downtown Boston, only 5 percent of those with credit scores fall into this same category.

In Springfield, Lawrence and Brockton, about 20 percent of those with a credit score have at least one account that is more than 60 days due, compared to 5 percent or less in Newton and Cambridge.

“There’s a lot of research from others that shows the benefits of mixed-income neighborhoods,” said Chakrabarti. “It would be a much better circumstance for the whole regional economy if things were less economically segregated, not just for these individuals, but for the whole regional economy.”

|

|