The refrain is the same, month after month: the pickup in foreclosure starts in Massachusetts is just “a paperwork problem.” But after almost two years, the same refrain starts to sound a little stale. And in fact, Banker & Tradesman has found, those new foreclosures aren’t all old defaults.

The oft-heard industry explanation is that when foreclosures were peaking in 2011 and 2012, mortgage servicing companies were busy processing so many foreclosures – indeed, thousands each month – that they made a lot of mistakes, some of which resulted in foreclosures being reversed in court.

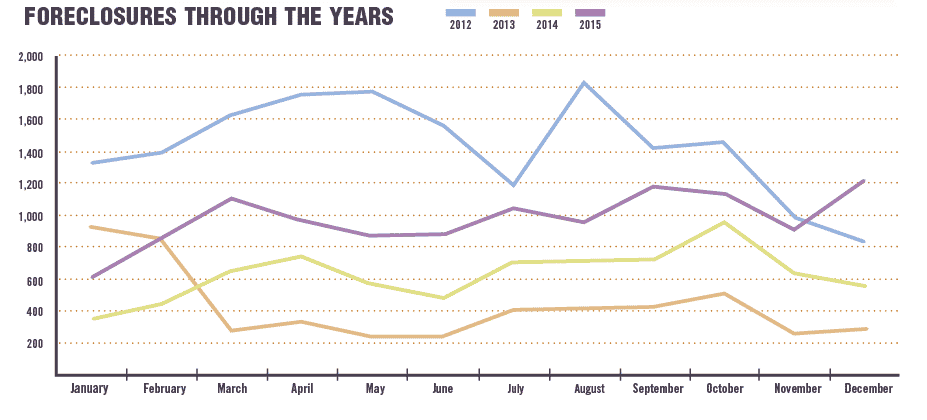

Because of that, and the fact that housing prices hadn’t recovered enough for lenders to break even at auction, foreclosures all but stopped until the second half of 2013, when they picked up again and have been increasing ever since. Industry insiders say the increase is due to the backlog of accumulated defaults that continued apace as foreclosures ground nearly to a halt.

Lenders overwhelming decline to speak publicly about foreclosures, recent or otherwise, but a spokesman for Wells Fargo, one of the largest lenders in the state wrote in an email, “We don’t publicly report on foreclosure and delinquency rates at the state level. However, our national delinquency and foreclosure rate continues to decline – a trend which we also continue to see in the state of Massachusetts.”

In its December 2015 Foreclosure report, CoreLogic, a property information analytics firm, confirmed that trend, but also revealed that while the news is good nationwide, the Bay State has both a higher foreclosure rate and a higher delinquency rate than the rest of the country.

The Massachusetts serious delinquency rate (90-plus days past due) is 3.4 percent, which is slightly higher than the national average of 3.2 percent, according to CoreLogic. The Massachusetts foreclosure rate of 1.3 percent is also higher than the national rate of 1.2 percent, according to the report.

According to data from the Mortgage Bankers of America (MBA) going back to 2002, delinquency rates in the Bay State have historically been lower than the national rate. That held true when the delinquency rates bottomed out during 2004 and 2005, and even when they peaked in 2009.

In the middle of 2013, something changed. As delinquency rates fell, the national rate fell faster than the Massachusetts rate, and the gap grew wider through the middle of 2015. Though the gap narrowed in the second half of 2015, the Massachusetts delinquency rate is still almost 17 percent higher than the nationwide rate.

From Every Walk Of Life

Median sale prices in the Bay State have recovered to about 96 percent of what they were at the peak of the market in 2005, according to data from The Warren Group, publisher of Banker & Tradesman, and many communities have exceeded those peaks.

Employment doesn’t explain the problem either. The unemployment rate in January 2016 was 4.7 percent, which is below the 4.9 percent national average, according to the Massachusetts Executive Office of Labor and Workforce Development.

Whatever the reason, one thing is clear: not all of the recent foreclosures are people who stopped paying their mortgages during the recession.

Methuen-based attorney James Bosco negotiates loan modifications and short sales for homeowners who are delinquent on their mortgages and facing foreclosure. He said the people who come to him for help are a blend of people who have recently become delinquent on their loans as well as those who haven’t made a payment in years.

“There were some hideous loans made during the boom,” Bosco said. “There was just so much of this that went on. The other part of it is individual circumstances. There’s a wide range of people who are delinquent because they might have lost their job, or because of health reasons. They’re from every walk of life, from factory workers to professionals.”

Bosco said that in some cases, the companies servicing the mortgage didn’t foreclose on the property as soon as they could have because they didn’t want it on their books; they were hoping the economy would turn around and the owner would catch up on their payments. Others who carrying subprime mortgages managed to keep up with the payments for years – until they couldn’t.

A True Story From Worcester County

Margaret – who requested that only her first name appear in this story – owns a home with her husband in Worcester County. They bought their current home at the end of 2005, after they received a purchase and sale agreement on the home they were selling. When that buyer failed to secure financing, the couple was forced to get a bridge loan to cover both mortgages until their first home sold. A year later, they sold their first home for $100,000 less than the asking price.

“In 2006, we knew we were in over our heads, so we started racking up credit card debt to pay other bills,” Margaret said. “We’re both well-educated and couldn’t believe we were in this situation. We couldn’t refinance our interest-only loan because we had negative equity, so we borrowed money from my folks, and muddled through until 2010, when we filed [for] bankruptcy.”

Margaret and her husband decided to exclude their home from the bankruptcy. They continued to make their mortgage payments on time and then, in December 2014, she was laid off. She called her lender to ask if there was anything they could do to help now that her family income was cut in half. The lender said no.

“We figured out a way to make it work, but then my husband got laid off in July 2015,” she said. “I called the bank again and I told them now we’re really in a quandary, is there anything you can do? The woman I spoke with said they didn’t have any programs for us. We’re really in a bind.”

Margaret said she thought the bank was doing her a favor by giving her a so-called “interest-only” loan. However, around the time the couple was out of work, the loan converted from interest-only to interest and principal, and payments are $4,000 a month.

“We were completely hoodwinked,” Margaret said. “We were sold something we would never be able to keep up with. We’re trying to work and figure something out. We have a child in college. They’re not willing to refi because we don’t have enough equity and they won’t accept partial payments. We’re trapped.”

Margaret said for a long time, she was embarrassed because she thought her family was the only one, but after a friend of hers met with others with similar stories at Worcester Anti-Foreclosure Team (WAFT) meetings, she felt validated. As she met more people in her family’s situation, validation turned to anger.

“We’ve all been sold a bill of goods because we didn’t exactly understand what we were getting into back in 2005,” Margaret said. “That’s no excuse, but we never should have qualified for the amount of money they were giving us in mortgage debt. Our lender was willing to work with us and we thought that was terrific. We’ve never missed a payment and never been late. This is going to be the first month.”

Margaret said her lender told her they could only help her after the loan has been delinquent for three months, so this will be the first month she doesn’t pay her mortgage.

“We’re scared to death to stop paying our mortgage,” she said. “The banks don’t care because they don’t have to. We agreed to pay it, but they also said they’d help us refinance in a year. They didn’t know the market was going to tank, but it’s disingenuous of them to not work with families who are trying to do the right thing. If we go into foreclosure, we will absolutely challenge it.”