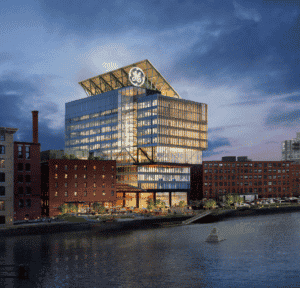

When it first moved to Boston, General Electric said it planned to build a 12-story, 800-person corporate headquarters on the Fort Point Channel before paring that back to leased office space for 250.

The rich subsidy package that brought General Electric’s headquarters to the Boston waterfront was not long ago hailed as a landmark win for both the city and the Bay State as a whole.

But two and a half years after the $145 million pact was first inked, the GE headquarters deal is an embarrassing fizzle that is fast on its way to becoming a major flop, at least when it comes to the hundreds of high-paying executive jobs GE promised to bring to the Hub and the fancy new tower it pledged to build.

GE’s stock price has cratered and the industrial giant is now on its second CEO since it announced plans to move its headquarters to Boston. And on the heels of its latest boardroom shakeup, all bets are off on the future of GE’s big hiring and building plans.

The GE mess offers a badly needed wakeup call, not just to Boston and the commonwealth, but to cities and states around the country that are desperately chasing similar deals.

When ambitious politicians chase high-profile economic development deals, the result too often is misspent attention and resources and, in the worst cases, the loss of millions of dollars in taxpayer money.

Scott Van Voorhis

Lack of Business Savvy

Politicians have a poor track record as investors, often picking the wrong company to back. Unfortunately much of today’s economic development – like the joint Boston/state campaign to lure GE from its long-time Connecticut home – involves betting on individual companies.

Companies shop around plans for new headquarters, plants, research complexes and distribution centers. And state and cities around the country compete with one another to land these deals, looking to outbid one another with the most generous package of tax breaks and subsidies.

In doing so, state and local governments effectively become investors in these companies, with hopes of being paid back not in profits, but in jobs created and taxes paid. But unlike venture capitalists and other investors, politicians don’t have the analytical skills or the necessary mindset needed to pick winners in a brutal global economy.

GE is a prime example. Yes, it’s an icon of American business, but it’s hardly a secret that GE has also been a company on a troubled track for many years.

Last November, barely 18 months after GE announced its move to Boston, CNN Business offered up an extensive take on the company’s mounting woes, “How decades of bad decisions broke GE.” And a year before GE’s Boston announcement, Forbes published a takedown of then CEO Jeffrey Immelt headlined “GE: A total leadership failure.”

The Forbes piece took aim at Immelt’s strategy of selling off pieces of the company – and hundreds of millions in real estate – in order to prop up the company’s stock price through a $50 billion campaign to buy back GE shares. That should have been a big, fat, flashing red warning sign for Boston and state officials as they courted and wooed GE.

No Incentive to Change

You can also rest assured that the GE mess will do little to dampen the appetite of state and local officials for pursuing the latest corporate headquarters deal. Unlike investors, politicians face few if any hard consequences for failure when it comes to pursuing high-profile economic development deals.

Things aren’t looking good at GE, but it has caused nary a ripple in the gubernatorial race as Baker gets ready to steamroll his hapless Democratic opponent in November.

Baker recently brushed off a question about GE’s woes with a broad comment on how big the company remains.

“The company’s still worth about $100 billion. It still has a huge footprint here in Massachusetts in health care and in green technology and in clean energy, and those industries are in very good shape,” the governor told reporters last week, per the Associated Press.

That’s because the public relations benefits of such big headquarters deals and other splashy economic development announcements outweighs the pain of their failure.

The economy and jobs are the number one concern of most voters, in both good times and bad. And being able to announce a deal to bring a big new company to town, with a lot of promised jobs, is a major PR coup for any politician. For your local pol, even the appearance of trying to boost the local economy in a concrete, easy to grasp way, regardless of results, is likely an overall plus with voters.

Except for a few business and political reporters and economic development specialists, few people are tracking these deals to see how they turn out.

The financial pain of any one deal falling through is hardly dramatic, either. In the GE deal, the state pledged $120 million in infrastructure improvements for the new headquarters complex, while the city offered up $25 million city property tax breaks.

Sure, it’s a lot of money. But it’s not enough to make dent in any single voter’s finances – and it’s certainly not enough to become a significant political problem.

The city tax breaks, in theory, are tied to GE following through on its pledge to bring 800 headquarters jobs to Boston, but we’ll see.

But there is a real cost to such deals, well hidden from the general public: the cost of lost opportunities.

As governors and mayors across the country chase after the latest hot company or project, they are squandering money, time and attention that would be better spent on shoring up the infrastructure and rules needed to support a thriving capitalist economy.

Maybe all the countless hours and millions of dollars spent pursuing GE were truly worth it.

But imagine if our governor and the mayor of our leading city had devoted the same amount of time to coming up with a blueprint for freeing our traffic clogged highways, fixing our broken public transportation system and clearing away barriers to new housing development in towns and cities across the state.

Maybe then our state and local leaders wouldn’t have to bribe companies like GE in order to get them to move here.

Scott Van Voorhis is Banker & Tradesman’s columnist; opinions expressed are his own. He may be reached at sbvanvoorhis@hotmail.com.

|

|