Rick Dimino

This fall, we are facing a choice between an outdated vision of the past and transformational change. It is an opportunity to learn from our past mistakes, build stronger neighborhoods, and listen to the hopes and voices of community leaders. If we prioritize future improvements to our transportation system, open spaces, while also protecting our water’s edge, then the choice is clear: Massachusetts should not rebuild an elevated section of the Mass. Pike as part of the Allston Multimodal Project.

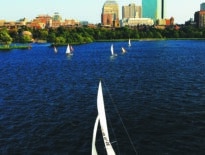

This is not just a highway infrastructure repair project; It is a city–building opportunity and a once–in–a–generation chance to recreate a new neighborhood in Boston centered around transit. If we get this right and build high-quality transit service and connections to other job centers in the regions, such as North Station and Kendall Square, we will all benefit for decades to come. There is also potential to create larger park space along the Charles River and protect bikers and pedestrians through new dedicated lanes.

Massachusetts is forced to act, because the elevated highway viaduct in Allston is becoming structurally deficient and must be either repaired or replaced in the next decade. So the fundamental question is: What is the top priority for this complicated, expensive infrastructure project? Should we concentrate on short-term impacts and potential disruption to the 100,000 vehicles traveling in this area each day, or should we set our sights on what we want when the project is completed? MassDOT will announce their final design plans in a few months.

A Bold Vision in Danger

Early last year, MassDOT announced a bold vision that would remove the elevated Massachusetts Turnpike viaduct and place its highway lanes alongside existing and proposed future commuter rail tracks. The benefits of these improvements include removal of the barrier created by the wide Turnpike viaduct between the adjacent neighborhoods and the river; improved connections and access to the river for pedestrians and cyclists; reduced noise impacts; and an opportunity to restore the river bank to improve the river ecology.

The potential for maintaining commuter rail service is also possible and the impact on the river can be minimized. This vision is crafted in way to be compatible with concurrent construction of West Station that will serve bus and rail connections for the neighborhood plus future development, and it can be completed quicker than the rebuild options.

These are only a few of the reasons to be excited about the potential of removing the elevated structure. Another surprising factor: taking down the viaduct may cost less than a rebuild. In both a lifecycle maintenance and initial construction costs, building the highway on the ground will be is less expensive for the commonwealth.

Unfortunately, last month MassDOT reversed course and now appears to favor rebuilding the elevated Turnpike viaduct, foregoing benefits of the earlier concept. Keeping an elevated Turnpike Viaduct squanders a once-in-a-century opportunity for Greater Boston, and runs in opposition to a large coalition of local and statewide organizations and residents of Allston, Brookline and Cambridge. MassDOT expressed strong opinions that options which place all or most of transportation elements on the ground, might require extensive environmental permitting because of the proximity to the Charles River.

Long-Term Vision Needed

There is nearly unanimous support from the community leaders, businesses, residents and advocacy groups that rebuilding the elevated viaduct is the worst possible option. A Better City serves on a 50-member I-90 Allston Interchange Task Force and helped to produce multiple design plans that would successfully create the infrastructure to do this project without an elevated viaduct. The urgency now to avoid a generational mistake is only going to grow over the next few months, but compromise is possible and must be reached.

Long-term benefits should outweigh any temporary disruptions when choosing design plans for major infrastructure projects.

Imagine if transportation leaders and elected officials had not eliminated the elevated Central Artery highway in downtown Boston just because there was not unanimous support for every aspect of the project, and instead took the easiest route for environmental permitting during construction phase. Boston would not see better transportation options, reconnected neighborhoods, cleaner air and the Greenway parks that include world-class public spaces and spurred significant private development.

In Allston, we must understand the choices today can lead to pride in our city and functionality for decades and set aside short–term simplicity and obstinate positions from a few outliers to building something special.

Of course, a full funding plan for this megaproject is not currently available, but the main decision on this structurally deficient asset will be made soon. Design plans for highways that were common 50 years ago are no longer the best option; instead we must set in motion a project that delivers the greatest long-term benefits to the city and region for the next century. If in a few decades, we are asking bikers and pedestrians to travel underneath a busy highway and we continue to block the riverfront from many Allston residents, as the latest alternative design proposes, we will have failed to do what we know is right. Let’s all see the big picture and find ways to make the right choice for our future in Allston.

Rick Dimino is CEO of A Better City.

|

|