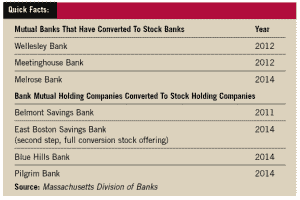

Seven mutual banks and holding companies converted to stock companies between 2010 and 2014, often an indicator that they may be fishing for a buyer. Four of those seven will complete the state-mandated three-year waiting period following the completion of an initial public offering, and be eligible for acquisition this year.

While two of those four – East Boston Savings Bank and Blue Hills Bank – already completed this waiting period in July and are not expected to be sold, the other two converts, Pilgrim Bank and Melrose Bank, will complete their waiting period next month.

These two smaller institutions, according to bank lawyers and consultants, are likely to draw interest from the bigger institutions looking to make an acquisition among a small pool of contenders in Massachusetts.

“The smaller banks are much more likely to be candidates for acquisition,” William Kozak, founder, president and CEO of WTK Associates, told Banker & Tradesman. “Mostly because of the way everything is structured today – the regulatory environment, the general competitive environment, the general cost of doing business and securing high quality management and staff – it is very difficult for a small bank to satisfy these issues or make acquisitions themselves.”

Approximately 60 to 80 percent of banks that undergo a standard conversion to stock form of ownership eventually are acquired, according to Arthur Loomis, president of Loomis & Co., a New York-based investment bank that has worked with community banks in Massachusetts on stock conversions and mergers and acquisitions.

Acquisition Indicators

Loomis looks for three main factors when trying to determine whether a bank is likely to be acquired: the age of a bank’s executive team and board of directors; the performance of the bank since issuing stock; and whether there are activists among shareholders.

Loomis looks for three main factors when trying to determine whether a bank is likely to be acquired: the age of a bank’s executive team and board of directors; the performance of the bank since issuing stock; and whether there are activists among shareholders.

If they are approaching retirement, a bank’s executive team and board of directors may be looking to cash out early and make profits in the short term.

Francis Campbell, 62, has been president and CEO of Pilgrim Bank since 2002, according to Bloomberg, and the age of Pilgrim’s directors ranges from 62 to 72.

When asked about the possibility of a merger, Pilgrim’s CFO Chris McCourt said he could not comment, but said to call back once the three-year waiting period and third quarter of this year ended.

Melrose Bank President and CEO Jeffrey Jones, 55, has been with the bank since 1987 and took his current role with the bank in 2001, according to Reuters. The ages of the board’s members range from 52 to 69.

Melrose has grown its assets about $95 million from the second quarter of 2014, around the time the bank went public.

But the bank’s return on assets at the end of the second quarter this year, at .75 percent, was below the average return on assets (.84 percent) for all banks in Massachusetts under $400 million in assets, according to FDIC data.

Pilgrim, who has also grown its assets close to $95 million since going public, has an even lower return on assets this year at .47 percent.

Both banks are overcapitalized, another factor Boston banking lawyer Kevin Handly said he looks at for acquisition targets.

The total risk-based capital ratio of Melrose is 19.5 percent and 15 percent for Pilgrim, meaning they have more capital on hand than is required, and therefore less capital generating growth.

“Overcapitalized, underperforming banks are often good acquisition candidates,” Handly said.

Both Melrose and Pilgrim also have activist shareholders.

A regulatory filing shows that Maltese Capital Management, which has supported activist campaigns before, has at least a 7.46 percent stake in Melrose Bancorp as of earlier this year.

Another regulatory filing from May shows that Lawrence Seidman, who has a history of investing in community banks that sell to larger institutions, took a more than 5 percent stake in Pilgrim Bank.

“Generally speaking, there is a lot of pressure on smaller organizations to perform,” Loomis said. “Economies of scale are driving M&A activity and considering all of these factors, Pilgrim and Melrose are probably the most logical acquisition targets of the four.”

Players On The Field

Mutual banks that convert to stock are frequently purchased because they can make shareholders – many of whom were initial depositors with the bank who acquired their stock cheap – good profits by being acquired.

Larger institutions making these acquisitions gain easy access to capital and can expand their footprint.

Belmont Savings Bank made an IPO in 2011. Wellesley Bank and Meetinghouse Bank followed suit in 2012. Of these three, only Meetinghouse has been targeted for acquisition, with East Boston Savings Bank publicly announcing its plan to acquire the bank in July.

However, many say Belmont Savings Bank, which has swelled from $700 million in assets in 2011 to more than $2.3 billion now, may eventually be a target.

EBSB and Blue Hills Bank have grown tremendously and reported solid returns on assets.

“If they were interested in being purchased, both East Boston and Blue Hills would be attractive acquisition candidates,” Handly said. “But I bet both would rather buy than be sold.”

Smaller banks under $1 billion in assets are more attractive acquisition targets right now, said Stanley Ragalevsky, a partner at K&L Gates who works in the global firm’s Boston office.

“The number of potential buyers are greater than potential sellers,” he said. “But you don’t see anyone trying to buy a $5 billion bank and that is because the $15 billion to $20 billion banks [that would be good buyers] do not appear to be in the market. There is, however, a surplus of buyers in the $1 billion to $5 billion range … with the capacity to buy a bank of under $500 million.”

|

|