The East Coast’s first master-planned business park was built on an abandoned gravel quarry in Needham in the 1950s, pioneering a new real estate model that would attract the expansion and relocation of manufacturers and researchers from urban centers. Image courtesy of Needham Free Library

Nothing attracts real estate development in Greater Boston more reliably than the imminent completion of a new public transit stop.

For much of the 20th century, however, it was the construction of America’s first beltway-style highway that gave rise to the burgeoning technology and defense industry clusters that established Massachusetts as an economic dynamo.

Initially dubbed the Circumferential Highway, Route 128 was designed to replace a network of increasingly congested local roads. It gave rise to office parks populated by defense and tech companies leveraging research from the region’s higher education system, most notably Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Route 128 companies pioneered modern conveniences transforming the lives of post-war suburbanites, from microwave ovens and instant cameras to video games and personal computers.

“A great talent pool wanted to live out there,” said Peter Cohan, an associate professor of management practice at Babson College. “People wanted to have families and plenty of space around their house and good schools. That’s why [companies] moved out there initially, and all of this talent followed.”

A New Development Model in Needham

An initial section of Route 128 was built between Wakefield and Danvers between 1936 and 1941, but further expansion was put on hold during World War II. The Massachusetts Department of Public Works adopted a state highway master plan in 1948, and construction of Route 128 resumed between 1951 and 1958.

Plans for the East Coast’s first master-planned business park began even before completion of the section of Route 128 that ran through the heart of the western suburbs. Gerald Blakely, who died in 2021 at age 100, was one of the first developers to grasp the significance and potential from construction of the new highway.

Blakely settled on a former gravel quarry in Needham as an ideal location for a new prototype of commercial development that would include warehouse, manufacturing and office space. At Boston-based Cabot, Cabot & Forbes, Blakely led the development of the New England Industrial Center on 140 acres near the Newton line.

The location had several advantages, according to CC&F CEO Jay Doherty. Spurs from freight lines could serve manufacturing companies within the park. Although the property was located in Needham, it was separated from the rest of the town by Route 128, minimizing concerns from Needham officials and residents about additional traffic.

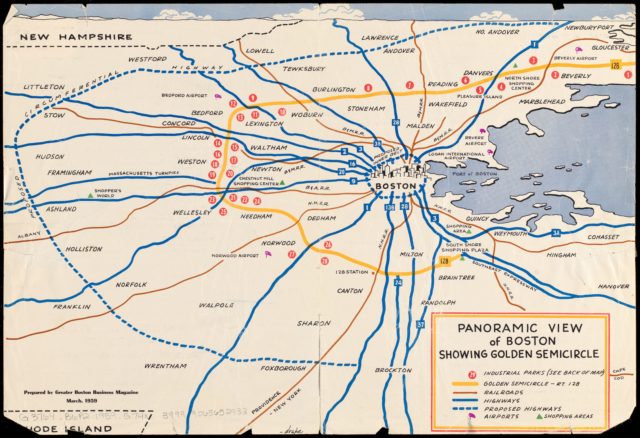

A 1959 issue of Greater Boston Business Magazine contained two-page map of the region’s “Golden Circle” showing industrial parks and shopping centers springing up around the under-construction Route 128 highway. Image courtesy of the Boston Public Library/Digital Commonwealth | Public domain

Predecessor to Silicon Valley

Construction of Route 128 had far-reaching effects that illustrated the public sector’s role in shaping economic development, said Anthony Flint, a senior fellow at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

“It was Silicon Valley before there was a Silicon Valley, and that investment was easy compared to some of the infrastructure we need today,” Flint said.

Route 128’s proximity to big parcels of former farmland allowed developers of industrial space to offer tenants an alternative to the traditional multi-story mill buildings of urban centers. New manufacturing plants were designed with more efficient layouts for receiving and shipping, CC&F’s Doherty noted. New prototypes included manufacturing space with showrooms in the front of buildings for visiting wholesalers and retailers.

As the son of an MIT professor, Blakely believed in the power of scientific research to drive economic development, and it shaped his sense of promising commercial sites. By the 1970s, CC&F owned dozens of business parks in Boston suburbs, developing facilities for major employers including Raytheon Corp., GTE and Polaroid. Cold War defense spending benefited MIT spin-off research centers such as Lincoln Laboratory and its non-profit MITRE Corp. Combined, the two labs employed 5,000 scientists in the mid-1960s, according to Susan Rosegrant and David Lampe’s “Route 128: Lessons from Boston’s High-Tech Community.”

Members of the Lexington Minute Men, led by Captain Fred Richardson, with drawn sword, march underneath a Route 128 overpass at the highway’s opening in 1960. Photo by James Roberts | Mass. Memories Road Show collection, UMass Boston digital collections

A Computing Cluster Spins Off

As defense spending waned in the 1970s, the minicomputer industry picked up the slack as a potent source of job creation in the western suburbs.

Kenneth Olsen, a Lincoln Laboratory researcher, had founded Digital Equipment Corp. at a former textile mill in downtown Maynard in 1957. The company grew explosively into the world’s second-largest computer company in the 1980s, spinning off dozens of companies that set up shop on Route 128 and Interstate 495. Rising competition led to layoffs in the early 1990s and DEC’s acquisition by Compaq in 1998.

As California’s Silicon Valley took the lead as the nation’s computing capital, Route 128 commercial real estate hit a plateau in the early 21st century. The city of Boston positioned itself as a model of urban revitalization, spurring a reverse migration by tech companies seeking to attract young employees who prefer to live and work in a city environment. Needham-based PTC relocated from a Needham office park to a new office tower in Boston’s Seaport District in 2017, while Amazon committed to occupy a pair of new Seaport District office buildings as it expanded beyond its Cambridge facilities.

Timeline: Real Estate and Banking’s March Through Mass. History

Life Science Fills the Gaps

Today, Route 128 and suburban Boston commercial real estate stands at another crossroads.

Traditional office tenants have been sorting through their space needs amid the widespread adoption of hybrid work models since the advent of COVID-19 in 2020. In 2021, Cambridge-based software company Pegasystems committed to 131,000 square feet at Hobbs Brook Real Estate’s 500,000-square-foot office-lab development at 225 Wyman St. in Waltham, as it switched to a hybrid model that company surveys indicated was preferred by employees. Pegasystems also leased a smaller office in Cambridge, giving employees a choice of suburban and urban offices to provide them with the most commuting options, Pegasystems Vice President of Real Estate and Facilities Dan Ryan said in an email.

“Employees’ desire for more flexibility was a key driver in devising our Boston region multi-office strategy,” Ryan wrote.

The coronavirus pandemic seems unlikely to reverse a generational preference for urban workspaces, particularly among younger workers, Babson’s Cohan said, as reflected by recent major expansion of life science firms such as Vertex Pharmaceuticals and Foundation Medicine in Boston’s Seaport District.

“I don’t see a big appetite in that generation for being out in the suburbs. My sense is the researchers are more likely to want to be in the urban area and not too far from Harvard and MIT,” he said.

Steve Adams

But COVID has also benefited Greater Boston’s suburban real estate as the Massachusetts life science industry seeks expansion after receiving nearly $19 billion in venture capital funding over the past 18 months.

Route 128 office parks are transforming into lab and biomanufacturing centers amid a pipeline of 40 million square feet of proposed and approved life science projects in Greater Boston, according to research by brokerage Newmark. Developers such as Greatland Realty Partners have focused on acquisitions and conversions of underutilized office properties in Lexington and Weston into lab space, while big office landlords such as Boston Properties have pivoted to lab conversions as a centerpiece of their suburban strategy.

“We see the importance of infrastructure to frame where companies thrive and do business,” the Lincoln Institute’s Flint said. “It was quite an intentional path all along that corridor. It was a lot of pavement and off-ramps, and a beautiful highway project, but that investment enabled and created the suburban residential and office and now lab landscape we see today.”