Foreign investors have acquired more than $7 billion in Greater Boston commercial properties since 2014.

The nest eggs of retirees from Ottawa to Brisbane increasingly rely on the financial stability of office towers in high-rent neighborhoods such as Boston’s Financial District and Cambridge’s Kendall Square.

Foreign investors – primarily retirement fund managers – have paid more than $7 billion to buy commercial real estate in Greater Boston since 2014. Downtown properties have become one of the most popular U.S. destinations for global capital as fund managers seek to juice up returns amid lackluster stock and bond markets.

Now cross-border investors have a fresh reason to bid up prices of real estate in the U.S.: the recent lifting of a 35-year-old tax on foreign entities, including pension funds, that buy majority stakes in U.S. properties.

“I’m sure it will help open the door a little bit more,” said Doug Jacoby, a senior vice president in investment sales at Colliers International. “It wasn’t stopping them before, but not putting limitations on them is going to be helpful.”

Coastal Cities As Safe Havens

Boston has been a hotbed of foreign investment in recent years, consistently ranked among the top four U.S. metros. Funds from Australia, Canada, Norway and Germany have acquired trophy buildings since 2014. U.S. real estate is perceived as a safe haven from instability in Europe and Asia and a better-performing asset than debt and equities.

The new landlords measure investment timelines in decades, not years, and appear prepared to ride out the ups and downs in the real estate cycle.

“I hope you’ll see us as a big fabric of the community here for the next 55 years,” Oxford Properties Group CEO Blake Hutcheson said at recent forum sponsored by the Boston-based Commercial Brokers Association.

Toronto-based Oxford Properties has acquired $3.5 billion worth of commercial real estate in Greater Boston, about one-fifth of its global portfolio. It paid a record price of $1,000 per square foot in November to buy 500 Boylston/222 Berkeley St., an office tower in Back Bay.

Hutcheson said Oxford, which manages the real estate portfolio of the Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System, feels good about its local acquisitions. Greater Boston’s tech cluster, financial sector and higher education concentration make it one of the top U.S. metros to invest in for the long haul, he said, and the properties are exceeding Oxford’s pro forma.

“It took us three years to find the right opportunity in Boston. For us to get in this game, we had to cut a check for seven figures,” he said, referring to Oxford’s 2014 purchase of a five-building office portfolio including elite tenants like Microsoft’s New England Research and Development (NERD) Center. “We love our position here.”

for seven figures,” he said, referring to Oxford’s 2014 purchase of a five-building office portfolio including elite tenants like Microsoft’s New England Research and Development (NERD) Center. “We love our position here.”

In recent years, foreign pension funds acquired substantial minority interests in trophy office towers including Atlantic Wharf, 100 Federal St. and 75 State St. Limiting their investments to minority stakes enabled them to avoid triggering the Foreign Investment in Real Property Tax Act.

In December, President Barack Obama signed legislation that puts foreign pension funds on an equal footing with their U.S. counterparts, exempting qualifying funds from FIRPTA. In the past, FIRPTA kicked in when foreign pension funds were selling real estate to U.S. buyers, and required the buyer to withhold 10 percent of the proceeds for submission to the IRS.

Even with the changes, foreign investors may still opt for joint ventures with U.S. companies, simply to tap into local operators’ expertise, Jacoby said.

“It depends on the (investor) group and the different mindsets,” he said.

Price Gap Widens Between City And Suburbs

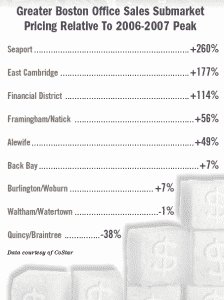

The global investment boom has contributed to a steep rise in prices of office buildings in downtown Boston. Buildings in submarkets like the Seaport District have been trading at more than twice the prices paid around the previous peak in 2006-2007, according to data from CoStar.

Prices of office buildings in some suburban markets, meanwhile, still trail pre-recession levels.

The wide city-suburbs price spread partially reflects such fundamentals as the rebound of downtown rents and occupancy rates, as urban office space steadily grows in popularity among companies recruiting Millennial workforces. The trend has seen multiple tech companies and investment firms move from Route 128 office parks to the city, and reached a watershed moment with General Electric’s decision to uproot its headquarters from a suburban Connecticut enclave to Seaport District.

In the suburbs, by contrast, many of the large recent transactions involved developers buying older properties with a repositioning play in mind. The strategy is common in suburban markets where most of the office product is more than 30 years old, and developers spend a significant chunk of their investment after the sale on renovations.

In recent years, Boston-based Davis Cos. has acquired aging office parks in Bedford, Burlington, Dedham, Medford and most recently Waltham, rebranding the complexes and adding fitness centers, cafes and outdoor amenities.

At 1025-1075 Main St. in Waltham, it saw an opportunity to get in near the ground floor of a suburban market that seems to be on the upswing, President Rich McCready said. The company paid $52.5 million, or $173 per square foot, for the former BayBank offices built in the 1980s.

It’s planning to modernize the conventional office space and attract additional tenants.

“All of those factored together and said to us we can transform the asset and get the lift of an area that’s transforming as well,” McCready said.