A northbound Green Line train rounds the curve at the MBTA's Boylston Street station. State House News Service photo / File

There’s been a springtime sense of optimism surging through major metropolitan area transit systems. Just not at the MBTA.

Ridership across the board remains depleted compared to before the pandemic, but at several other agencies, the years-long recovery has reached new peaks.

The New York City Subway hit 71 percent of pre-COVID ridership on March 16, drawing a celebratory press release from Gov. Kathy Hochul. Amid cherry blossom season in the nation’s capital, the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority provided 405,000 heavy rail trips on March 23, a post-pandemic record that prompted GM Randy Clarke to proclaim “it’s busy out there!”

Here in Massachusetts, with incoming MBTA General Manager Phillip Eng preparing to take the reins, the performance provides little cause for celebration. Ridership on the MBTA’s core subway system has languished amid months of disruption, including safety-related closures and staff-related weekday service cuts. More recently, slow zones have spread across the system, even as passengers continue to flock to the commuter rail in growing numbers.

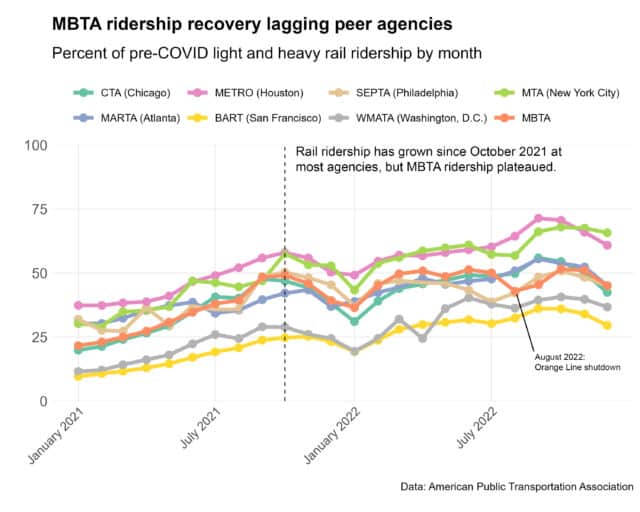

While most transit agencies have experienced seasonal ups and downs in ridership, they appear to be on a gradual upward trajectory from the spring 2020 lows. The T’s subway system, by contrast, is stuck on a plateau: the four major lines collectively hit a high of about 55 percent pre-COVID average weekday ridership in October 2021 and have not advanced much beyond that milestone in the 16 months since then.

“I think it has to do with the fact that the T is unreliable and infrequent and people don’t trust it. They don’t think that they’re going to get where they need to go safely or reliably nor efficiently or speedily,” said Brian Kane, executive director of the independent MBTA Advisory Board that represents cities and towns who help fund the agency. “It used to be that if you had a choice, many people would take the T. Now folks have a choice, and they’re not.”

Ridership growth at the MBTA has slowed since the fall of 2021 while other agencies have sustained momentum, a trend that advocates attribute to numerous service, safety and reliability issues at the T. Image by Chris Lisinski | State House News Service

The T still falls in the middle of the pack against peer agencies in terms of overall ridership recovery, or how average crowds today compare to baselines set before the pandemic rewired work and travel patterns.

In December 2022, the MBTA reported providing about 333,200 light and heavy rail trips on an average weekday, roughly 45 percent as many as it did on an average weekday in February 2020, according to data compiled by the American Public Transportation Association.

Among three dozen agencies with similar APTA light and heavy rail data available, that rate ranked 25th, just ahead of Philadelphia’s SEPTA (44.9 percent, Chicago’s CTA (42.5 percent) and well ahead of Washington, D.C.’s WMATA (36.8 percent).

However, the MBTA has not been able to sustain the same kind of rebounding momentum as other metro transit systems, particularly amid the seemingly nonstop upheaval last year that included a Federal Transit Administration safety investigation, a month-long Orange Line shutdown and heavy rail service cuts that persist to this day.

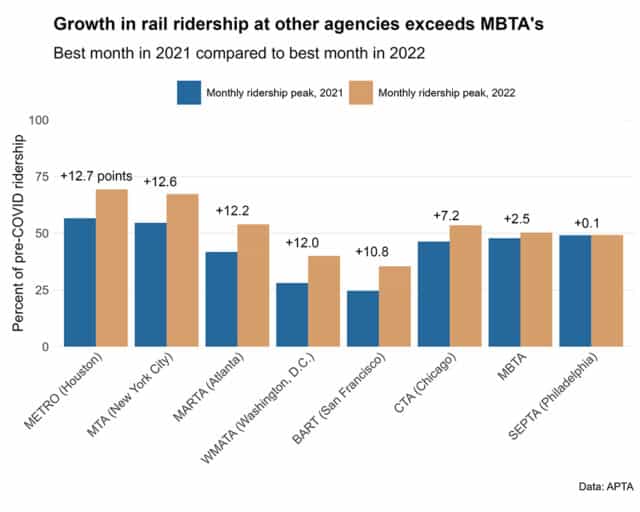

The lag is apparent when comparing each agency’s best performance in 2021 to its best performance in 2022. WMATA maxed out at 28 percent of pre-COVID rail ridership in 2021 and 40 percent in 2022, a peak-to-peak growth of 12 points. From annual peak to annual peak, Houston’s METRO grew 12.7 points, Atlanta’s MARTA grew 12.2 points, San Francisco’s BART grew 10.8 points, and Chicago’s CTA grew 7.2 points.

APTA data, which differ slightly from MBTA figures, estimate the T’s light and heavy rail ridership in 2022 topped out at 50.3 percent, only 2.5 points above its 2021 peak.

Among 35 agencies with similar data the News Service analyzed, that rate ranked 33rd, ahead of only the 0.5 point growth at SEPTA and a drop in peak rail ridership at San Francisco’s Muni system.

The MBTA’s average weekday ridership grew only 2.5 percentage points from its best month in 2021 to its best month in 2022, significantly less than the increases most peer agencies reported over the same span. Image by Chris Lisinski | State House News Service

The most recent APTA figures only run through the end of 2022, but as CommonWealth Magazine reported on Friday, data compiled by TransitMatters board member Chris Friend indicate MBTA weekday subway ridership fell as far down as 45 percent of pre-COVID levels in mid-March amid widespread speed restrictions.

“We are seeing ridership reach pre-pandemic levels in New York City, yet here, the stagnant ridership is a clear result of the perception of safety, poor reliability, service cuts, slow zones and painful diversions,” Jarred Johnson, executive director of TransitMatters, told the MBTA’s board late last month. “We are nearly nine months into service cuts on rapid transit and more than a year into bus service cuts. This board needs a laser focus on hiring and service quality, not talk that reeks of managed decline.”

‘This Is Existential For The Commonwealth’

While public transportation ridership remains persistently depleted across virtually all agencies, the greater Boston region’s notorious roadway traffic has already come roaring back. Department of Transportation officials expect they will collect 99 percent as much toll revenue as before COVID hit.

Kane suggested the divergent trends for transit and highways suggest that the T has failed to win back “choice riders,” who have multiple commuting options, and is currently serving only those who effectively rely on the trains and buses.

He argued, like some business leaders and Gov. Maura Healey herself have in recent months, that the MBTA plays a key role in the region’s economic success, particularly due to the high cost of living here.

“I mean, Kendall Square doesn’t exist without the Red Line being able to move folks around and get folks in and out of work. If we’re rapidly approaching – or in the case of the T, un-rapidly – a state of being where the public transportation system cannot do that, that is just another reason for folks not to want to work here or not to be able to attract the talent to come here and work and live and play and do all the stuff that we like to do,” Kane said. “I really do think this is existential for the commonwealth.”

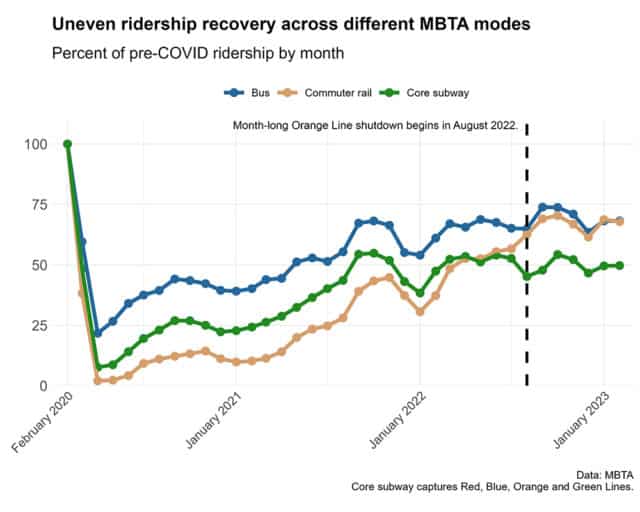

The recent slowdown has not been as significant on MBTA buses, which since the very first days of the public health emergency have retained the highest share of riders of all public transit modes.

MBTA data show average weekday bus ridership hit about 68 percent of pre-COVID levels in October 2021, fell more than 10 points that winter, reached a new high of nearly 74 percent in September and October 2022, and since then have dipped back down a bit to about 68 percent.

Commuter rail, meanwhile, stands in contrast to both subways and buses. Its average ridership is the lowest of the three primary modes, but it has displayed undoubted success at attracting passengers since the lowest of the lows.

While the T’s subway ridership has plateaued over the past year-plus, the bus network has maintained some momentum and commuter rail has grown even more significantly. Image by Chris Lisinski | State House News Service

As recently as March 2022, the commuter rail system had a lower rate of ridership recovery than both MBTA subway and buses. And since the turn of the year, it’s been effectively tied with buses for the best rebound, attracting about 68 percent as many passengers in February 2023 as it did in February 2020.

Pragmatism, or Defeatism?

MBTA officials are aware that the ridership recovery has slowed. Earlier on in the process of building back from the pandemic, they built out three models – one optimistic, one moderate and one pessimistic – for what fare revenue might look like.

Through the first half of fiscal year 2023, actual collections lag even the worst of those three “scenarios,” prompting the T’s budget-writers to suggest using an even lower fare revenue figure in the next budget.

Low ridership carries fiscal consequences: in FY19, the last full year before the pandemic, fare revenue represented 31 percent of all revenue in the T’s operating budget. Agency officials expect they will face a shortfall of hundreds of millions of dollars in the coming years if ridership does not rebound.

MBTA Board of Directors Chair Betsy Taylor in early March described the sluggish outlook as the “new normal,” drawing criticism from one of the region’s most prominent business voices, Greater Boston Chamber of Commerce President Jim Rooney.

Rooney told the News Service he believes the T’s recent lag behind other transit agencies is partly because MBTA higher-ups have not “embraced a culture of being a driver of the economy.”

“The T positioned itself as a victim of COVID instead of part of the solution to help our economy recover from COVID. When you hear the chair of the T board discuss the ridership as the new normal, that’s concerning. That’s not the way it should be,” Rooney said. “Some of it is because the culture has been defeatist. It’s been accepting that these ridership levels are here to stay. I’m not accepting that.”

“If you put the kind of service schedules – let alone reliability, because they can’t even meet the schedules – that say if you can’t catch this train, you’re going to wait 20 minutes on rapid transit and an hour on commuter rail, people can’t rely on that, can’t build their lives around that,” he added. “Then you add the lack of reliability, and it’s chaos.”

Taylor and other MBTA officials defended their approach late last month, saying at a March 23 board meeting that they view their embrace of a lower fare revenue projection as a pragmatic budgeting move rather than an admission of defeat.

“I think it’s important to set reasonable expectations for the revenue that is coming in. If we gain more revenue, that will be a good thing, but to put ourselves in a position where we might have to make cuts in important operations mid-year should we not be successful in changing the revenue would be very harmful,” Taylor said. “I appreciate the great deal of thorough research that has been done. I appreciate that this is not a statement of the desired amount of ridership or revenue, nor is it a statement of the service that will be proposed in this budget. It is rather an intelligent, prudent estimate of what the revenue will be.”

The T continues to budget for a full slate of pre-pandemic service, though both buses and subways continue to operate on reduced frequencies amid agency-wide staffing shortages that officials have failed to fill and the safety-related slow zones blanketing all four subway lines.