One of downtown Boston’s trophy office towers, 75 State St. rose amidst a 1980s scandal that engulfed some of Massachusetts’ top real estate and political figures.

As the owners of 75 State St. prepare to recapitalize the downtown Boston office tower, the city’s high-end commercial real estate is increasingly dominated by global institutional investors.

While 75 State St.’s ornate granite facade with its gold-leaf decorations betrays its 1980s roots, it remains a desirable investment. It’s currently 98 percent leased and the current owner, Brookfield Properties, has reached an agreement to recapitalize the property at a price of $635 million, or approximately $755 per square foot, according to real estate industry executives.

But unlike other downtown trophy properties, 75 State St. rose even as a scandal involving politics and real estate threatened to topple some of Massachusetts’ most powerful figures.

A City Monetizes Parking Garages

In the 1980s, the financial constraints of Massachusetts’ new Proposition 2½ property tax law and a reviving downtown Boston development scene set the stage for the 75 State St. scandal. It spanned more than five years of backroom dealings and two years of civil litigation out of the public eye, followed by an abrupt settlement less than a month after details surfaced in the press. Players included the powerful state Senate President William Bulger, Boston’s biggest apartment landlord Harold Brown and an Assistant U.S. Attorney named Bill Weld.

Brown, a Dorchester native and MIT graduate, began assembling his real estate empire in the 1950s and was the largest residential landlord in Boston by the 1970s. He began expanding his downtown holdings in the mid-1970s, acquiring properties in what legal filings at the time described as a “rundown” section of lower State Street near the elevated Central Artery.

Harold Brown

Real estate development was far from a slam-dunk in 1970s Boston, but there were signs of revitalization. The 1976 opening of the new Faneuil Hall Marketplace and Quincy Market brought millions of tourists to the surrounding neighborhood. And developers had proven there was a market for new office high-rises, with the completion of the 53 State St. tower in 1977 and groundbreaking of the 40-story Exchange Place tower at 60 State St. in 1981.

Brown’s instincts paid off in November 1982 when the Boston Redevelopment Authority – now the Boston Planning & Development Authority – sought proposals from private developers for four city-owned garages, including the Kilby Street Garage just off State Street. The dispositions were part of the city’s strategy to offset tax abatements it owed commercial landlords after Proposition 2½ took effect.

A development and design pamphlet issued by the BRA sought a mixed-use development including offices, housing and ground-floor retail space. It sought designs that blended with the surrounding neighborhood and architecture, while minimizing wind tunnels and shadows.

The proposals for the various properties attracted a who’s-who of renowned architects. One of the potential designers for a competing developer was Benjamin Thompson, whose Cambridge-based Architects’ Collaborative designed the new Faneuil Hall Marketplace. Another was Moshe Safdie, part of Boston Properties’ team. Brown trumped them by partnering with architect Graham Gund of Cambridge and Equitable Life Insurance. Perhaps more importantly, Brown’s ability to combine the two-thirds-acre garage parcel with his own holdings provided an advantage in the BRA’s selection process, which gave developers the option of including adjacent properties.

A Friend of Bulger’s Intervenes

Beginning in December 1983, as the BRA was evaluating developers’ proposals, Thomas E. Finnerty Sr., a former law partner of Senate President Bulger, met with Brown to discuss the project. Two starkly divergent accounts of Brown and Finnerty’s discussions later emerged under oath.

In December 1983, the BRA tentatively designated Brown as developer, with plans to combine his parcel at 89 State St. and one on Doane Street with the city garage to create a 1.1-acre site for a 24-story office tower.

Finnerty claimed that Brown in 1984 had agreed to pay him $500,000 for his share of the joint venture, based upon a formula reflecting the total square footage approved for the tower and its rental income upon attaining 90 percent occupancy. The agreement called for additional scaled payments for square footage exceeding 500,000 square feet.

After the Beacon Cos. agreed to buy Brown’s land assemblage in 1985 for $28 million, Finnerty demanded another $1.3 million from Brown, arguing that he was entitled to additional payment based upon the size of the building, which would eventually reach 31 stories and 841,000 square feet. Having failed to receive the additional payment, Finnerty filed a civil suit in May 1987. In a counterclaim, Brown argued that the agreement with Finnerty was illegal.

“Finnerty stated and implied that government approvals of the project would be in jeopardy unless a financial arrangement satisfactory to him was made,” Brown’s attorneys wrote.

Brown’s legal team, led by prominent Cambridge defense attorney Harvey Silverglate, commenced discovery of Finnerty’s financial activities. A subpoena of bank records produced a check from a realty trust controlled by Finnerty to William Bulger for $215,000.

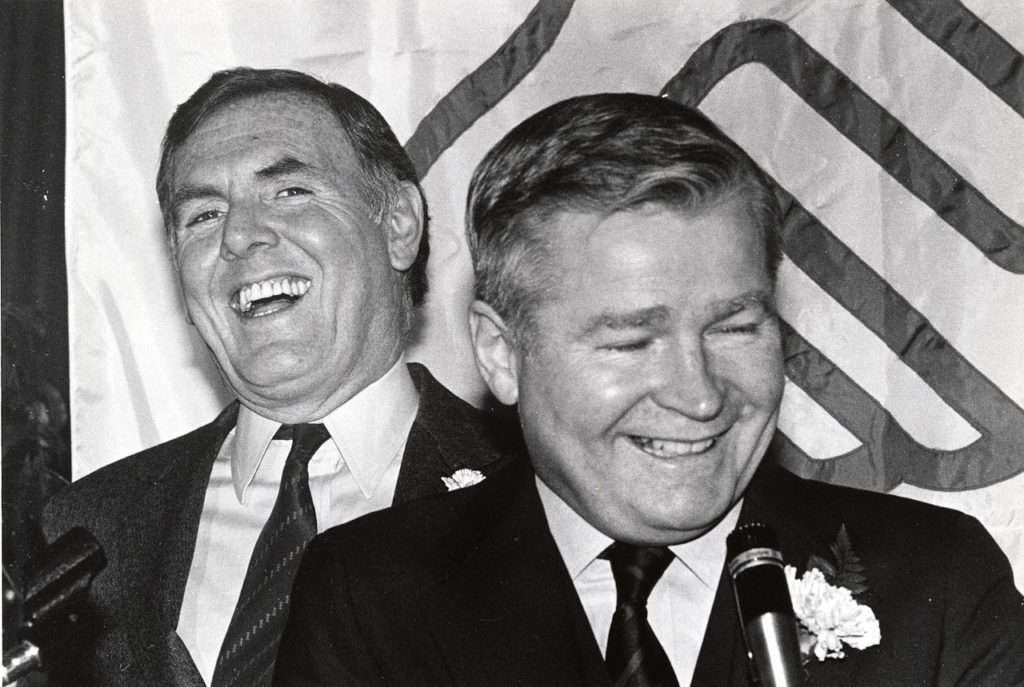

Boston Mayor Ray Flynn and Senate President William Bulger, right, laugh during a political event in the 1980s. Photo courtesy of the city of Boston Archives

Bulger described the transactions as a loan from his longtime friend and business partner related to unrelated legal work. In a deposition, Bulger said Finnerty told him in mid-October 1985 that Brown was the source of some of the funds, and that he repaid the money on Nov. 17 and Dec. 4.

In an era before online court filings, the explosive allegations escaped public scrutiny until Dec. 8, 1989, when the Boston Globe Spotlight team unleashed details in a page-one bombshell headlined, “The Deal Behind a Skyscraper.”

Reporters Dick Lehr and Gerard O’Neill detailed irregularities in the dispute, including developers’ failure to list Finnerty as having an ownership interest in 75 State St. Days later, Brown’s legal team asked the court to authorize additional discovery of Finnerty’s finances, seeking to determine if he invested in other real estate ventures benefiting Bulger.

And they offered an alternate explanation for what prompted William Bulger to repay the realty trust in 1985: fear of entanglement in a federal investigation. Three days earlier, Assistant U.S. Attorney William Weld had brought an indictment against Brown for bribing a Boston city councilor, and a subsequent Boston Globe article had referenced possible payments to other unspecified elected officials.

“Brown submits that up to that point there was nothing … which would have alarmed Sen. Bulger or Finnerty about the 50-50 split of Brown’s money in which they were engaged,” attorneys argued.

And then suddenly, it was over.

Case Dismissed

Citing a desire to avoid a protracted legal battle and to focus on his business, Brown agreed in late December to a settlement in which he would pay Finnerty an additional $200,000. The case was dismissed in January 1989. Then-Attorney General Scott Harshbarger wrapped up an investigation in 1992 and declined to bring any charges.

Brown died in February at age 94, a year after retiring from The Hamilton Co. He never wavered from his account of why he had a change of heart. In one of his final interviews, published in 2016 in the Brookline Tab, Brown scoffed at speculation that he had been threatened by Bulger’s brother Whitey, the South Boston crime boss. He described Finnerty as a lobbyist, in contrast to his legal filings that complained of extortion.

Steve Adams

Silverglate declined to comment when contacted by Banker & Tradesman, saying he interprets attorney-client privilege to continue after the client’s death. Finnerty could not be reached for comment.

75 State St. is reportedly under agreement, approximately a year after owner Brookfield Properties placed it on the market. According to The Real Reporter publication, the property is being recapitalized. The new investors will be a partnership of Allianz Life, a German insurer, and Beacon Capital Partners, the same company that originally bought the development site from Harold Brown in 1985.

Finnerty was disbarred in 2008, after advising his client John Bulger, Whitey’s brother, to lie to a grand jury about the mobster’s disappearance. Supreme Judicial Court Associate Justice Elspeth Cypher reinstated Finnerty’s law license in May 2018, citing his pro bono legal work and volunteerism at a hospice. On the Dorchester law firm’s website, Finnerty’s biography starts off by noting that he co-founded the firm with William Bulger in 1962.

|

|