In one classic example of poor timing, the Boston Convention and Exhibition Center was at one point forced to shut down construction to head off a $100 million overrun.

There’s a big reason why public construction projects so often wind up blowing budgets, and it’s one that is so obvious it’s amazing it never really gets debated: Really bad timing.

Everyone has their own pet theory about what has caused the huge construction pileup at UMass Boston that has blown a $30 million hole in the finances of the city’s only public research university, from a ban on bids by non-union contractors to mismanagement at the top.

But putting all that aside, one thing stands out: After a decade of planning, fundraising and construction of other new buildings, UMass Boston is just now gearing up to replace its crumbling underground garage, a project that has the potential to be the school’s own mini-Big Dig.

Timing may not be everything in life, but it is often crucial, and nowhere as much as in the construction industry, where prices for raw materials – and the availability of workers to do the job – follow mostly predictable, cyclical patterns.

And with developers across Boston competing in one of the tightest labor markets in years for the crews needed to build, this is absolutely the worst time to begin work on any project, let alone a fairly complicated one.

“We are just talking to a developer who is having trouble getting bids from subcontractors,” said David Begelfer, chief executive of NAIOP Massachusetts. “In some cases, it is being able to get the workers, period, at any cost.”

If you need evidence of how time equals big money in Boston’s perpetually overheated construction market, look no further than plans by Las Vegas tycoon Steve Wynn to build a posh gambling resort just over the Boston line in Everett.

Wynn had hoped to break ground not long after being awarded a license in September 2014 to build his Boston-area casino, only to be faced with nearly two years of legal battles with officials in neighboring Boston and Somerville.

Since then, the price tag for Wynn’s project has ballooned from $1.7 billion in 2014 to $2.4 billion today – a stunning, $700 million jump! The increase alone is enough to build a tower – or maybe would have been a decade ago.

Not Just UMass

Still, UMass Boston is hardly alone in pushing ahead with big construction plans at the worst possible time – in fact, it happens so often with big projects relying on the public purse that is more the norm than the exception.

A bigger and much more significant case in point is the Green Line Extension, which came close to being canceled last year after estimates pointed to the potential for a huge budget blowout that would have turned the $2 billion project into a $3 billion one.

Now the plan to extend the Green Line 4.7 miles from Lechmere Station on through Union Square and other parts of Somerville to Medford is back on after some tough value engineering. Plans for enclosed stations have been stripped down and replaced with open air platforms, among other things.

It didn’t need to be this way. State officials agreed to the Green Line extension all the way back in 1990 to head off an air-pollution lawsuit by environmental activists over the Big Dig.

The project then languished for nearly a quarter of a century until 2014, when the state agreed to finally move ahead with the project after being hauled into court again.

One can only imagine how much the project would have cost if it had been built a decade or two earlier – certainly taxpayers wouldn’t have to shell out $2.3 billion as they are now. Given how real estate values have shot the moon near Davis Square in Somerville and other Red Line stops, the Green Line Extension would have more than paid for itself with the real estate boom it would have unleashed.

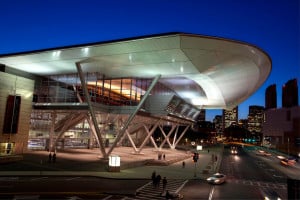

Maybe the classic example of the bad timing that seems to plague so many large public construction projects though is the Boston Convention and Exhibition Center.

State lawmakers gave a green light to the aircraft-carried sized meeting hall in 1997, but construction didn’t get underway until the early 2000s. The state board overseeing the project was at one point forced to temporarily shut down construction to head off a looming $100 million overrun.

Construction budget overruns, whether at UMass Boston, the Green Line Extension or the convention center, fuel public anger and cynicism about big public infrastructure projects and feed a perception of gross mismanagement of public dollars. It is a vicious cycle, with each public construction overrun making it harder to win support for future projects.

The answer isn’t to shy away from building badly needed public infrastructure, but rather to find a smarter way to do it. An awareness of the timing of big projects – and how that timing can have a dramatic impact on the cost – would be a great place to start.

Ideally, big public infrastructure projects should be launched during down economic times when there’s slack in the labor market and material prices are cooling. You don’t necessarily need a crystal ball to time things right – it would have been more cost effective to rebuild that crumbling UMass Boston garage pretty much any time over the past decade compared to now.

Not only would UMass Boston have been able to take advantage of a more favorable labor market, borrowing costs were also skidding along at all-time lows.

So timing may not be everything, but it can be darned important when it comes to the cost of big public construction projects.

|

|