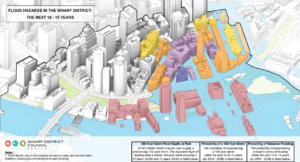

Boston’s Wharf District Council released a scenario of how coastal storms could inundate properties as it lobbies for construction of an $877-million flood barrier.

A study commissioned by the nonprofit neighborhood group recommends a 1.5-mile flood barrier including elevating portions of the Boston Harborwalk, as rising seas more frequently encroach upon the downtown waterfront.

“This new graphic is going to explain to people who are on the other side of the Greenway how incredibly vulnerable they are, and to what extent,” said Marc Margulies, Wharf District Council president and a Boston architect.

After receiving an earmark from the state legislature, the group hired consultants Arup to develop models of how rising sea levels will affect the waterfront and portions of downtown during astronomical high tides and coastal storms.

The latest graphic includes projected flooding to properties based upon projected sea level rise and an event similar to 2018’s Winter Storm Grayson.

Properties including the Harbor Towers condominiums, New England Aquarium and Long Wharf Marriott hotel would become virtual islands under similar conditions by 2034, consultants project. Flooding would affect properties as far inland as Congress Street.

The first phase of the engineering study by Arup, completed in May, recommended construction of a $877 million floor barrier along 1.5 miles of downtown waterfront.

The study also predicts that “sunny day” tidal flooding will infiltrate highway tunnels and the MBTA Blue Line by the 2040s, and properties on the inland side of the Rose Kennedy Greenway by the 2060s.

With sea levels expected to rise up to 51 inches by 2070, flooding during a major storm could cause $3.9 billion in property damages, the report concluded.

The report recommended an initial $250-million initial phase of flood barriers in the area of Long Wharf, Central Wharf and Harbor Towers.

The Boston Harborwalk currently ranges from an elevation of 7 to 12 feet, and will need to be raised to approximately 19 feet across the district, the report said.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which is developing a citywide resiliency strategy for Boston, is expected to be the lead agency on the project, Margulies said.

But the project needs to overcome significant regulatory and funding hurdles.

In recent months, Wharf District Council representatives met with regulatory agencies to sound them out on any major impediments to the plan.

“We have gotten fairly universal acknowledgement that what we’ve proposed is permittable. That doesn’t mean it’s a slam dunk or there won’t be any discussion,” Margulies said.

Sources of funding, and how the project ranks compared to other resiliency projects, is undetermined. The mayor’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

The city has commissioned its own series of neighborhood-based coastal resiliency studies in recent years, and is also studying how to protect Long Wharf because of its importance as a tourism and transportation hub.

Last month, the Boston Planning & Development Agency’s Long Wharf resiliency consultants warned that construction of permanent flood barriers will be difficult because of the location of the MBTA Blue Line tunnel and regulations preserving access to the waterfront. Consultants Kleinfelder predict annual property damages in the Long Wharf area of $137 million beginning in the 2030s.

Some activists are lobbying for creation of a new state-level agency modeled upon the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority to oversee resiliency projects.

In November, Gov. Maura Healey announced creation of a new chief coastal resilience officer position at the Office of Coastal Zone Management to oversee projects protecting the state’s 1,500 miles of shoreline.